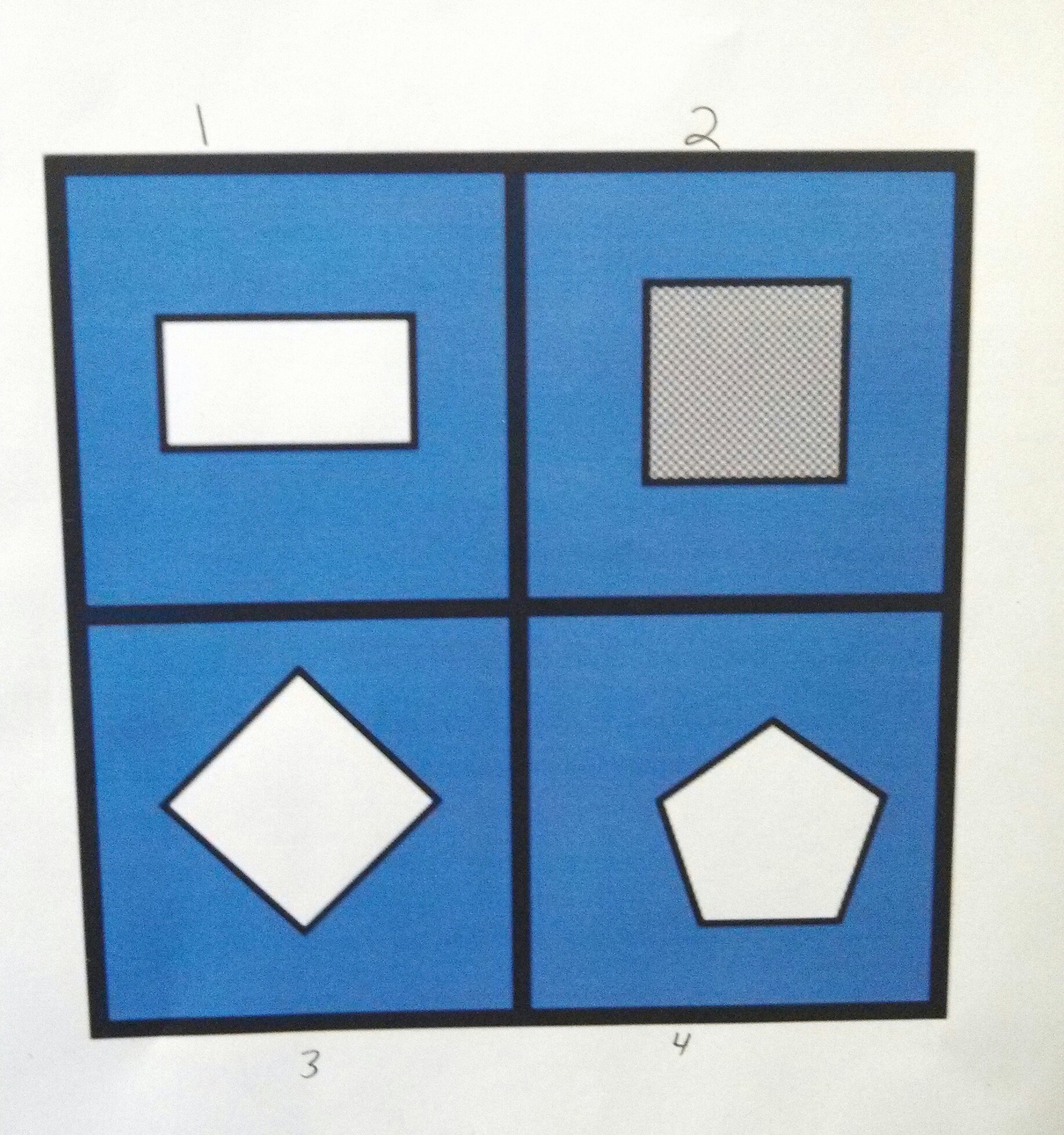

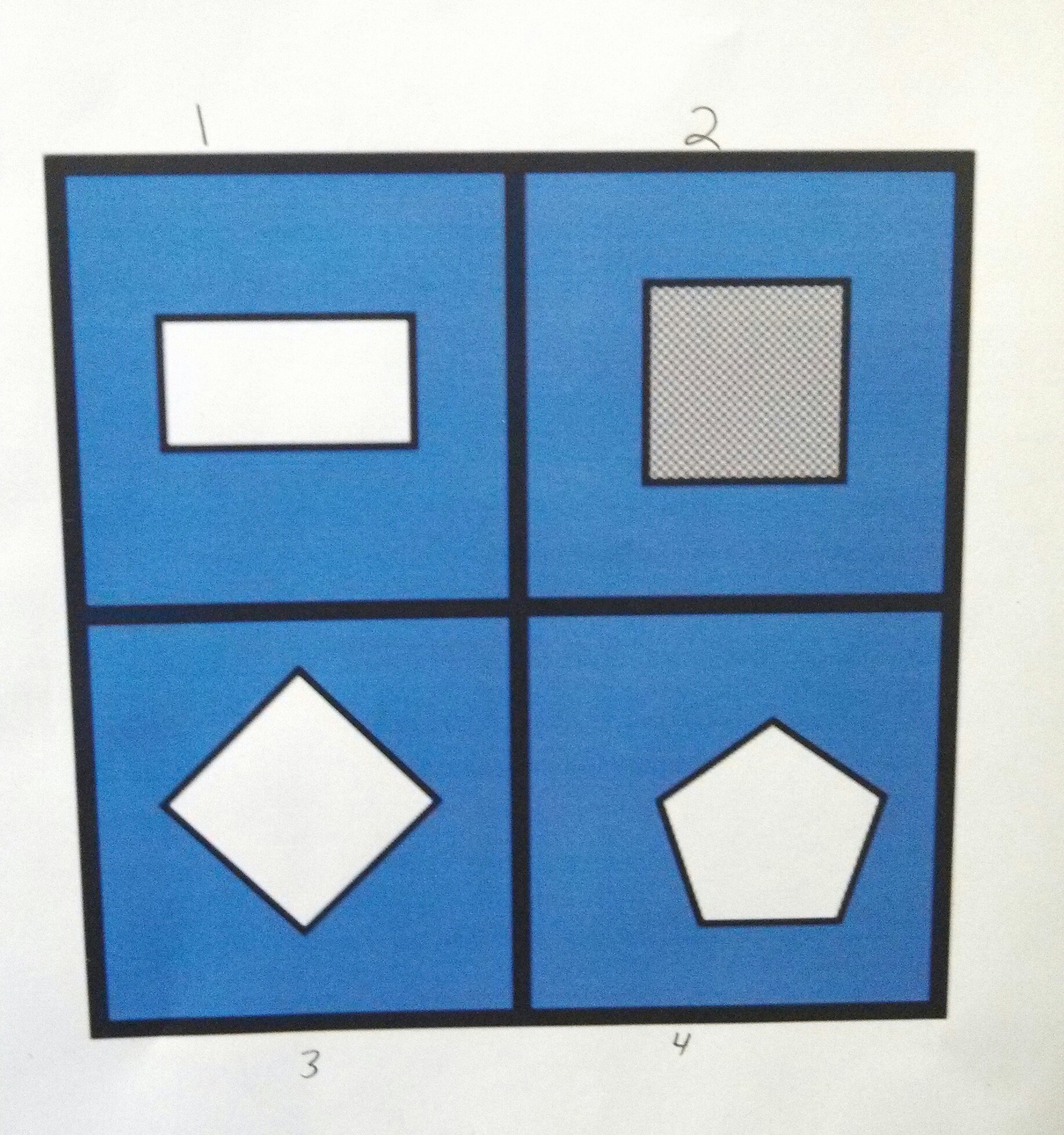

I visited a first grade last week, and the teacher asked me to take over an already-in-progress Which One Doesn’t Belong? (#wodb) conversation with a small group. She’d chosen this image, shape 2 from Mary Bourassa at wodb.ca.

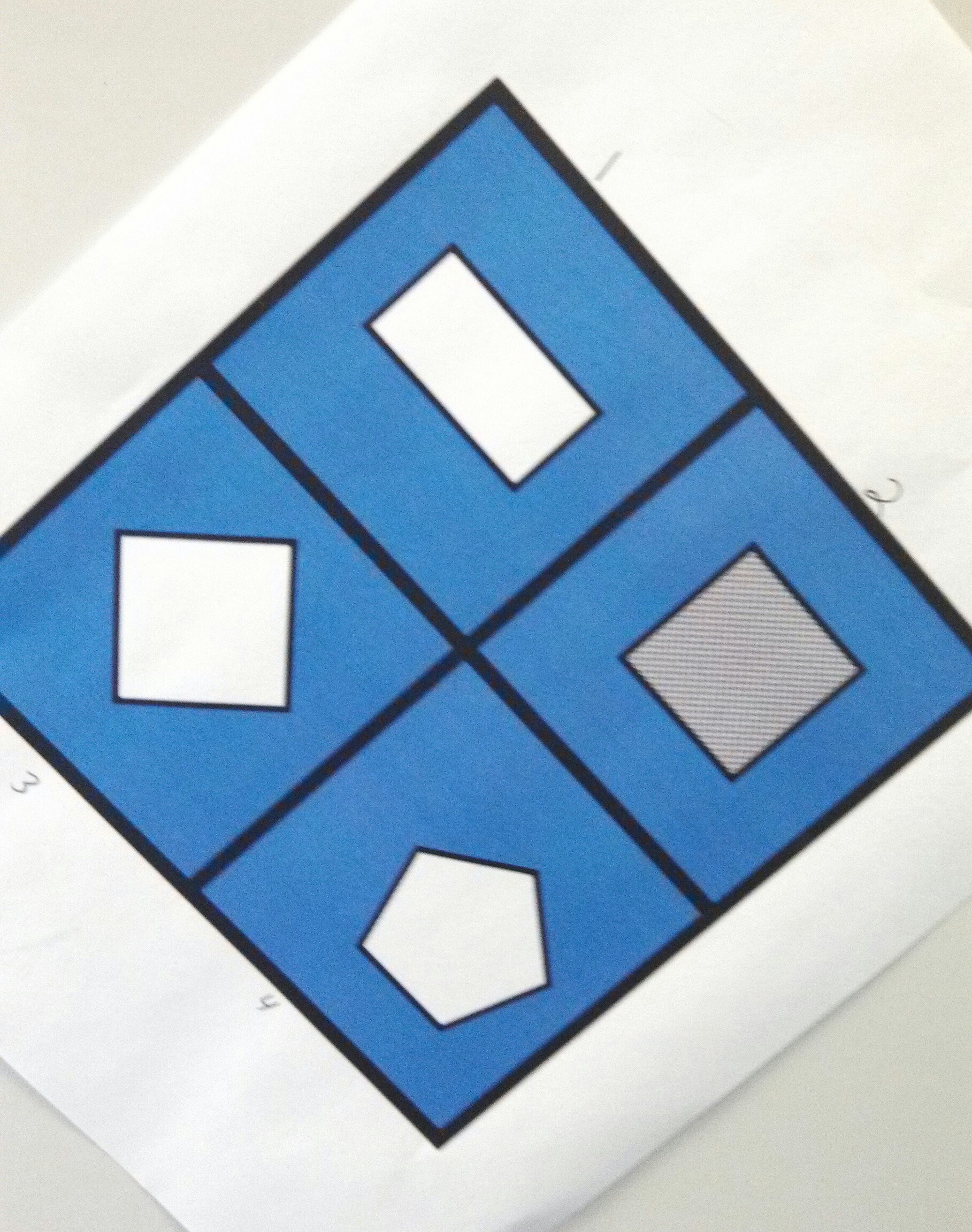

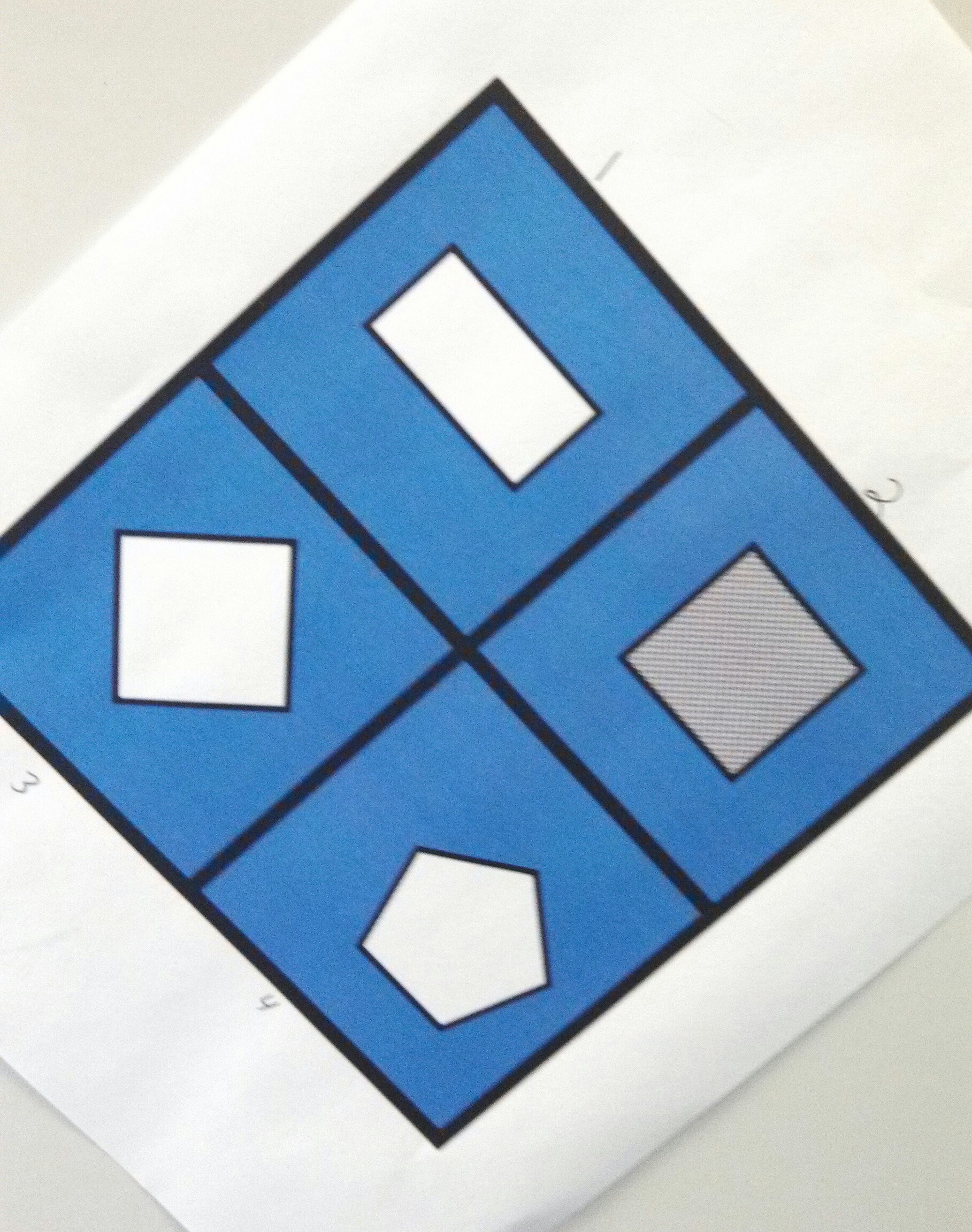

I’d heard the last couple of comments, and noticed kids were referring to these shapes rectangle, square, diamond, and pentagon. I know that children are usually describing shape and orientation when they use the word diamond, so the first thing I did was turn the page 45° to see what would happen.

Abby said, “Now you turned the gray one into a diamond and the white one into a square.” The other kids nodded their agreement.

I have learned so much about this moment from Christopher Danielson. In his brilliant book, Which One Doesn’t Belong? A Teacher’s Guide, he digs into the mathematics of diamonds and rhombuses, children’s informal and formal language, and how we might teach in a moment like this. My favorite sentence, which is pinned above my desk at work:

I have come to understand that talking about this difference is more important than defining it away.

Earlier in my career, I would have been tempted to define it away. With Christopher on my shoulder, I engaged the kids in a #diamondchat instead. I drew a quick #wodb with a rhombus, a kite, a diamond-cut gem, and a baseball diamond. I asked, Which of these shapes are diamonds? We played around with the word and I learned a lot about their thinking. Mario looked unsettled and said, “Now I’m not so sure what a diamond is.” He turned to me and asked, “What’s a diamond? Which one is right?”

I said, “I don’t know. It’s up to you.”

The kids gasped.

I smiled and went on, “Diamond is a great word. We can use it to talk to each other so people understand what we mean. But it doesn’t have a strict definition in math, like some other words do. For example, the word ‘square’ has a meaning in mathematics, and we can all agree on that meaning. But diamond isn’t like that. Its meaning is really up to you and what you’re talking about. If you think this is a diamond, it’s a diamond.”

Students liked this idea.

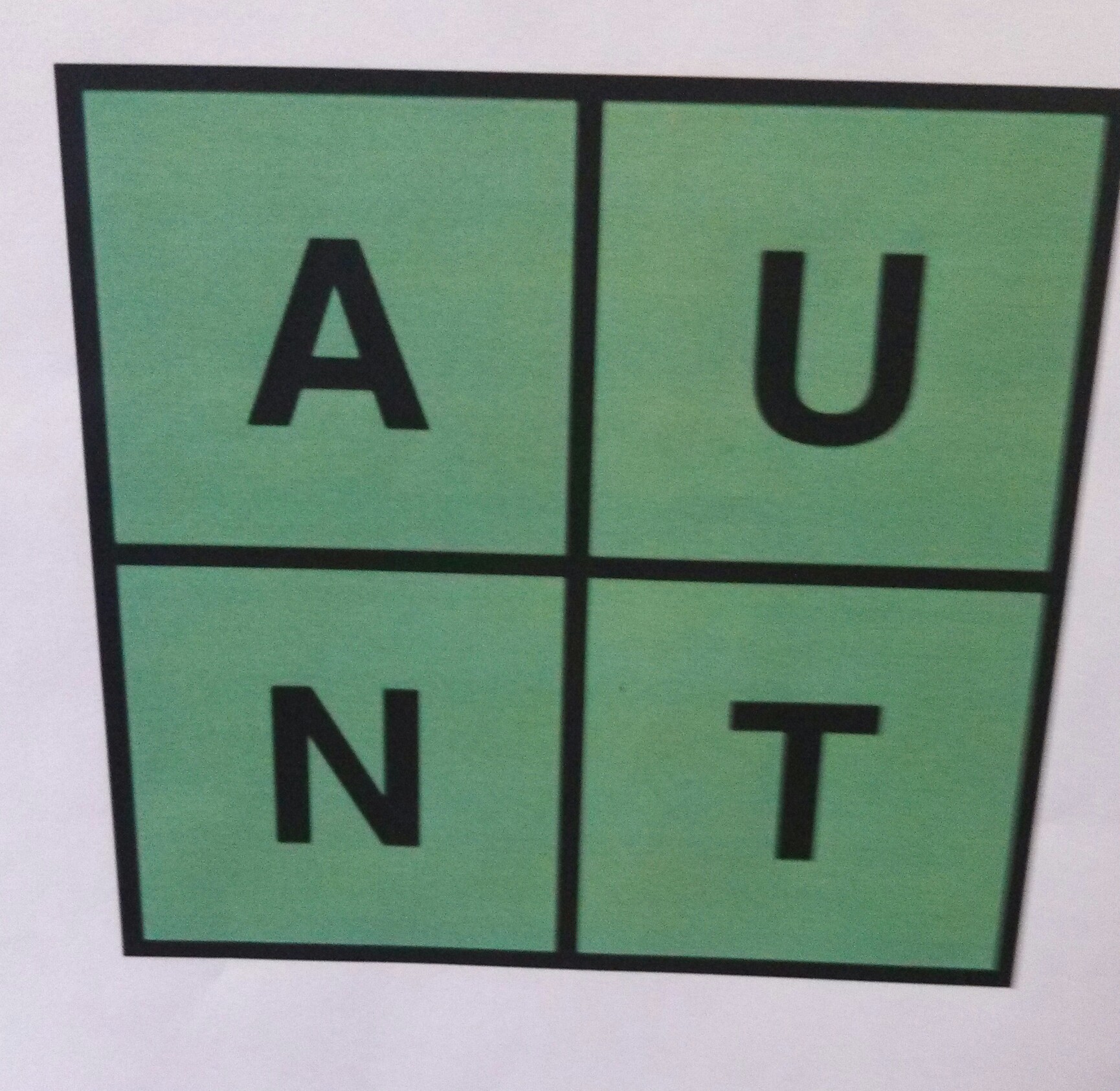

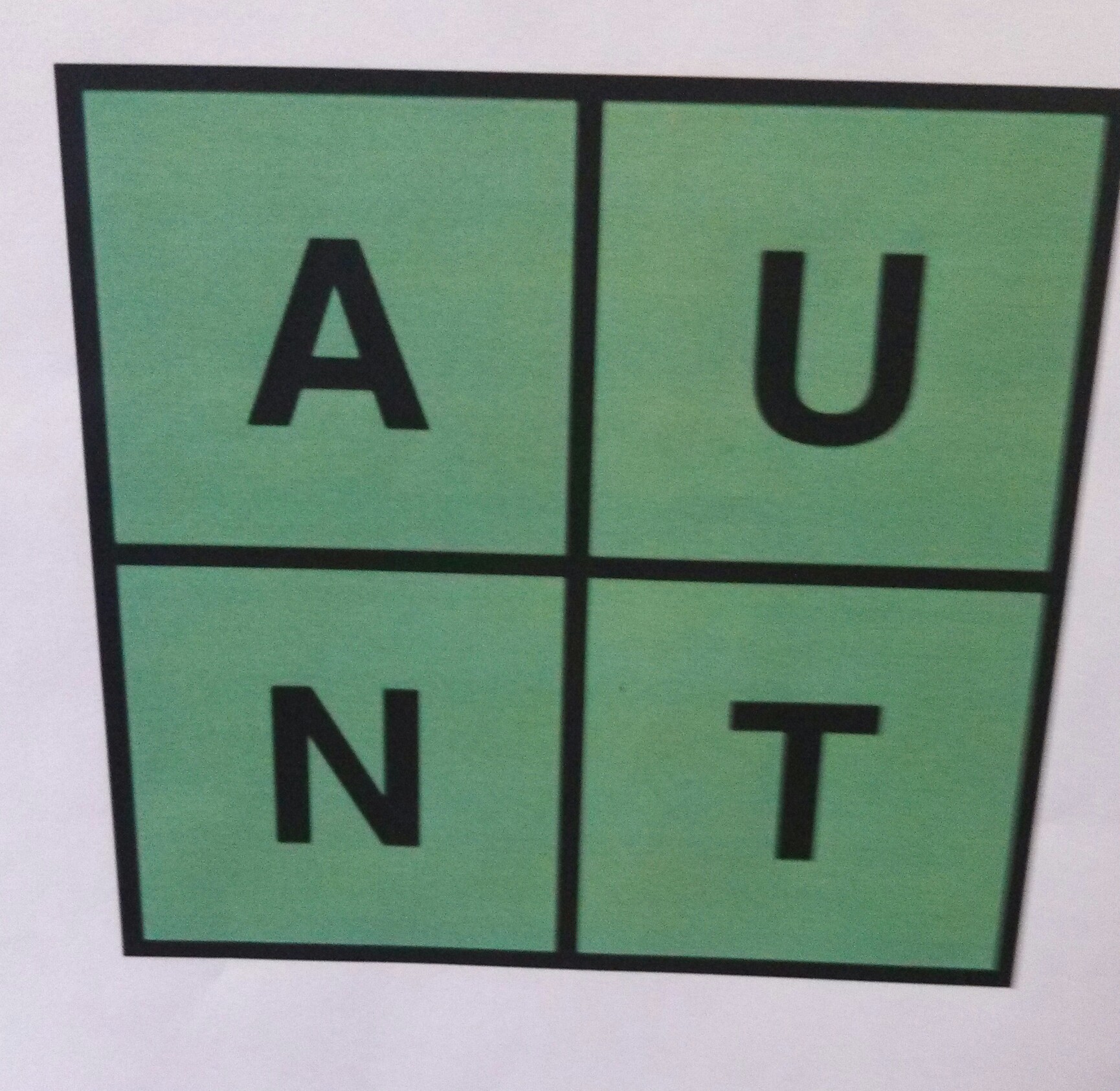

It was time to move on to a new #wodb, so I looked through the ones the teacher had printed out, and went for something different:

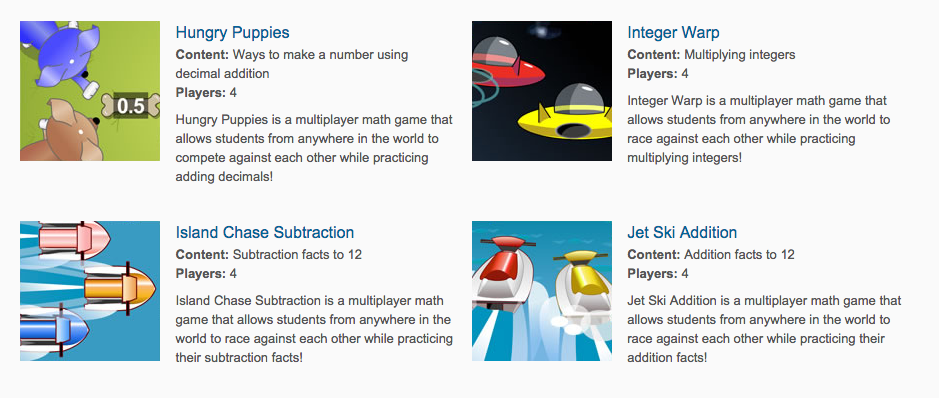

This one is from Cathy Yenca. It produced the desired effect right away:

Rianna: “I thought we were talking about math! Why’d you put this up! There are no letters in math!”

Mario: “Well, I guess you could think about them as shapes. Like U doesn’t belong because it has two lines and then a curvy handle thing at the bottom. And A doesn’t belong because it has an inside space. And T doesn’t belong because it’s the only one made out of 2 straight lines…”

Abby interrupted, “T only has 1 straight line.”

This one caught me off guard. “What do you mean?”

She gestured up-and-down with her hand and said, “That’s a straight line, and then it has a bar across the top.”

I asked, “How many straight lines does the N have?”

Abby: “Two.”

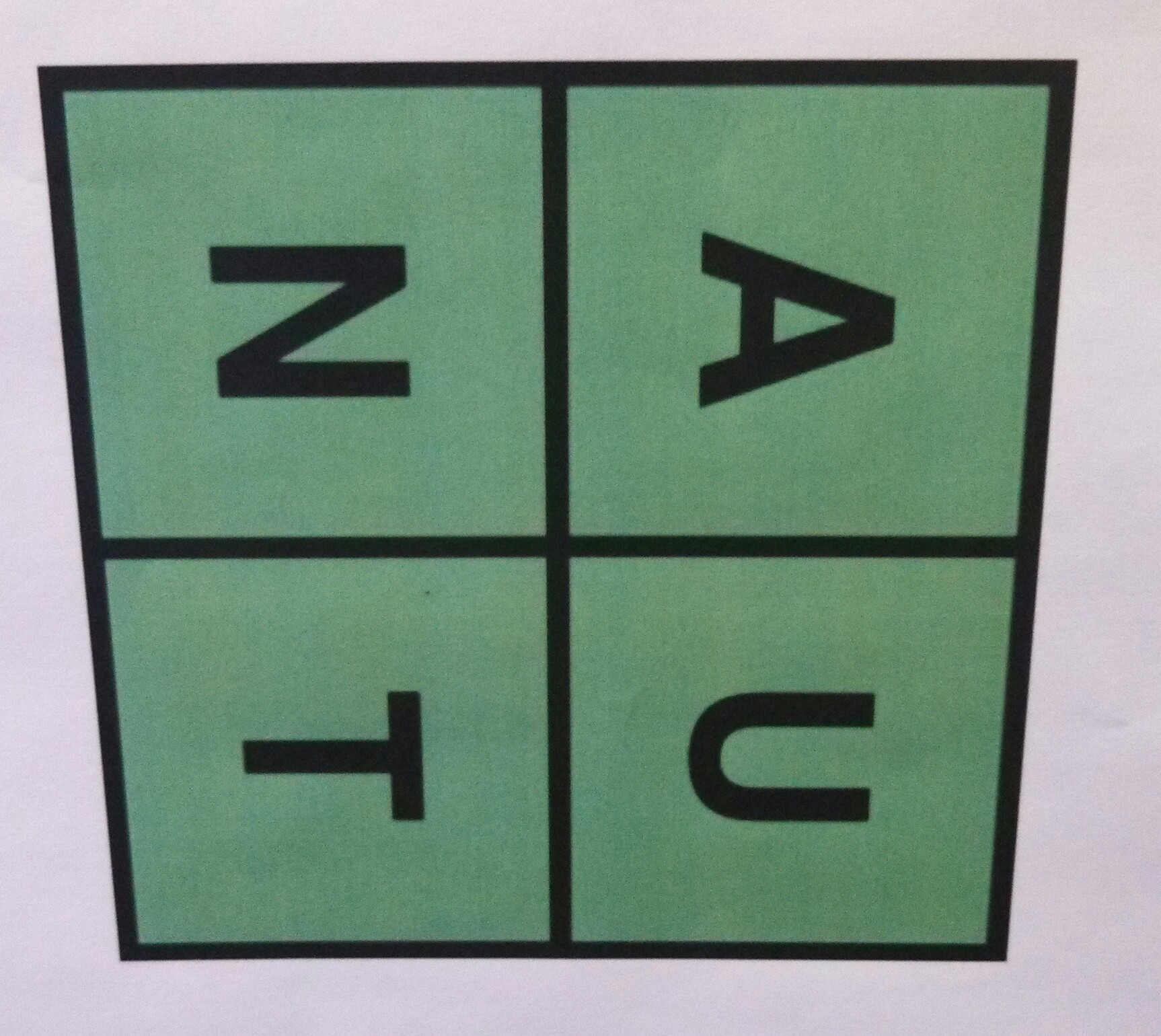

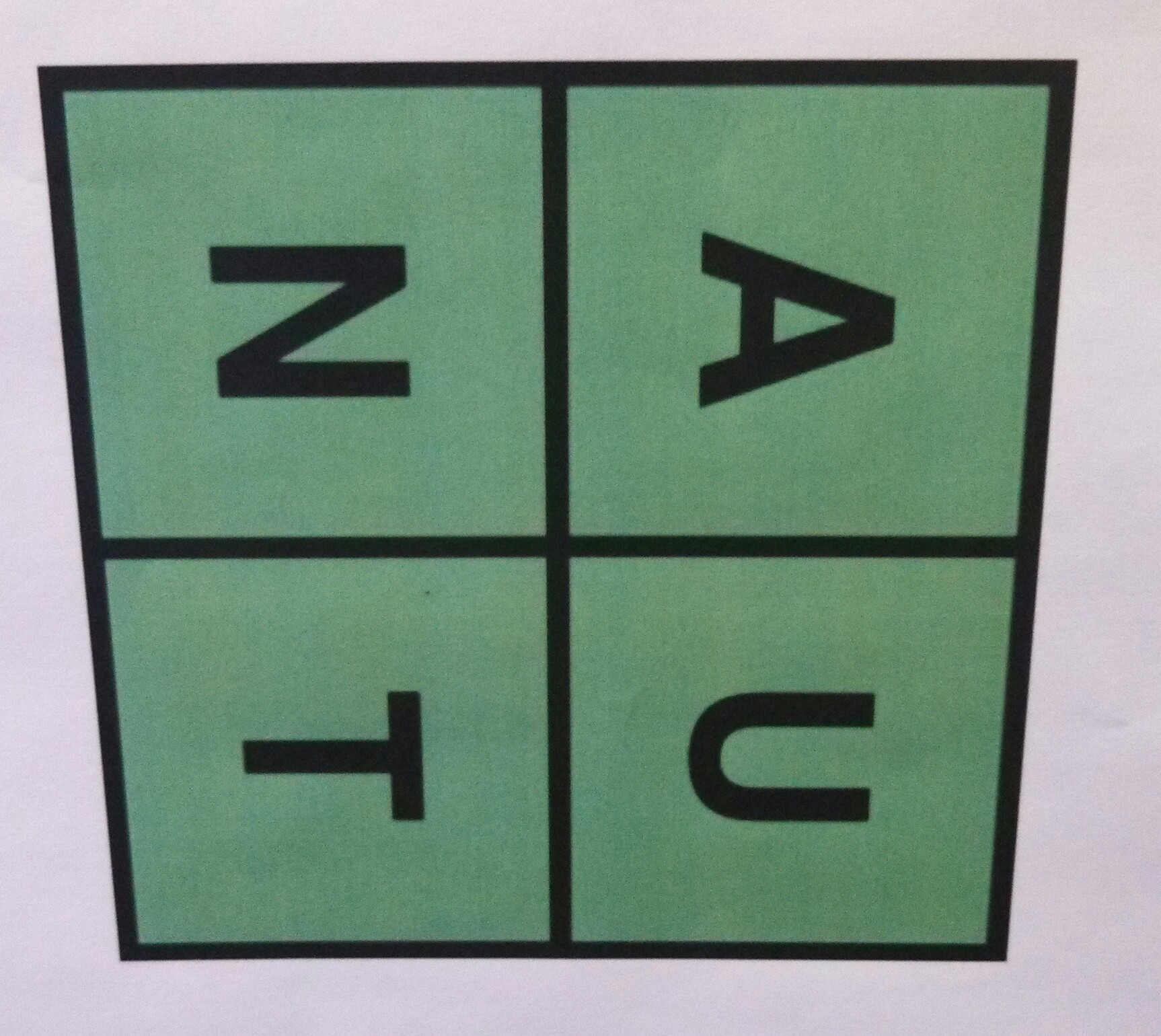

“What about now?”

Abby: “Now the N doesn’t have any straight lines.”

“What about the T now that it’s turned?”

“It still has one straight line, but now it’s that one.” She pointed to the now-vertical part of the T.

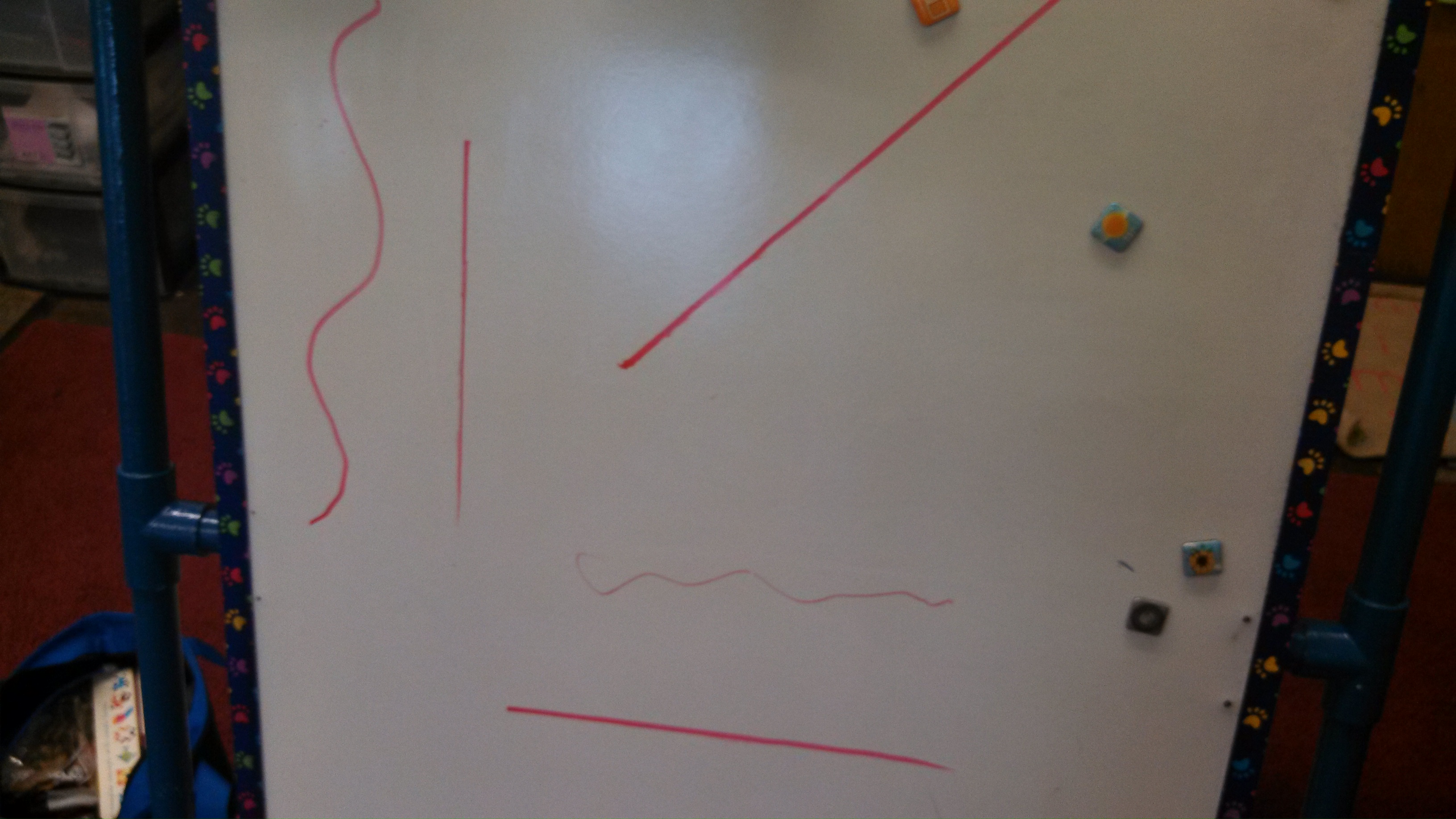

I pulled out a marker. “Is this a straight line?”

Abby: “It’s pretty close.”

“Right. Pretty close. Pretend I’d made it perfect.”

“Then yeah, it’s a straight line.”

“What about this one?”

“That’s a laying-down line.”

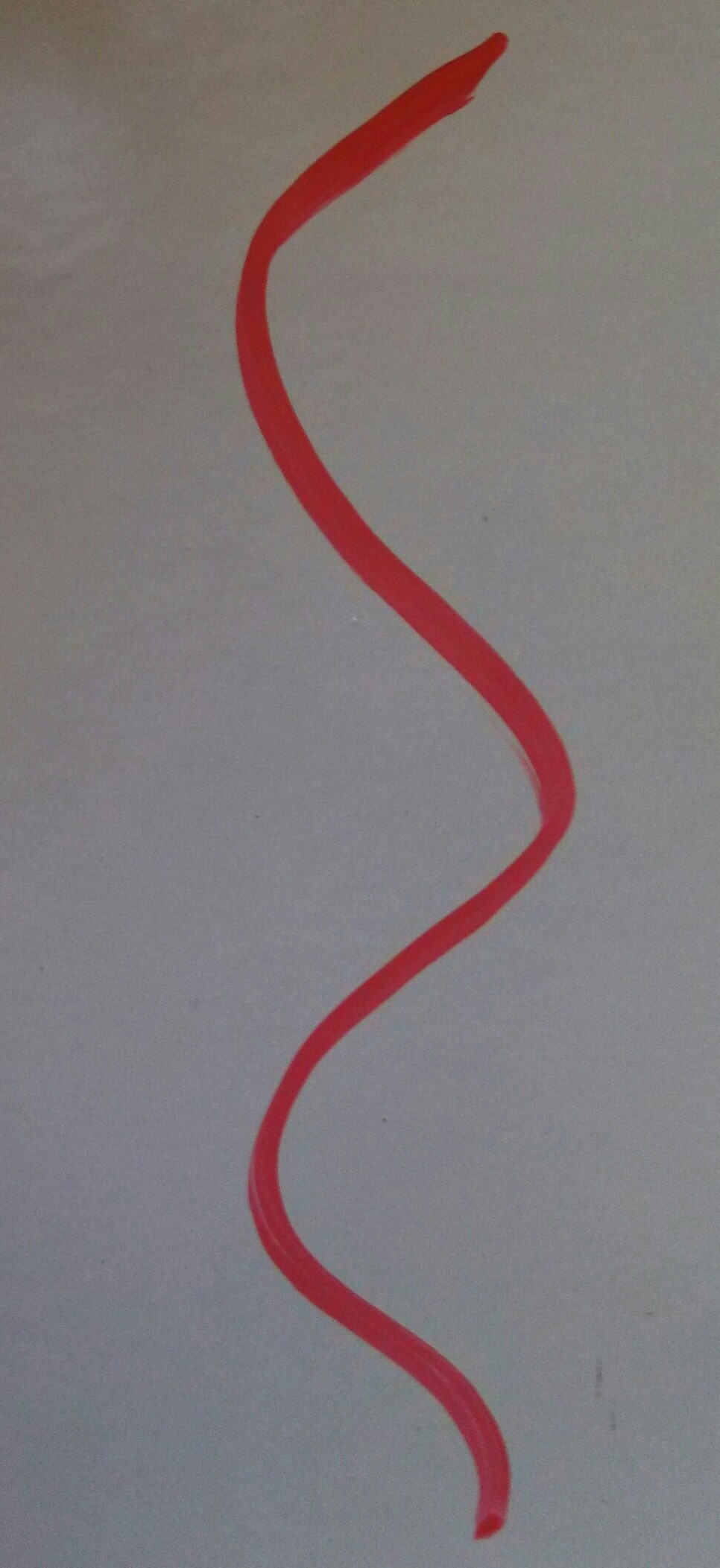

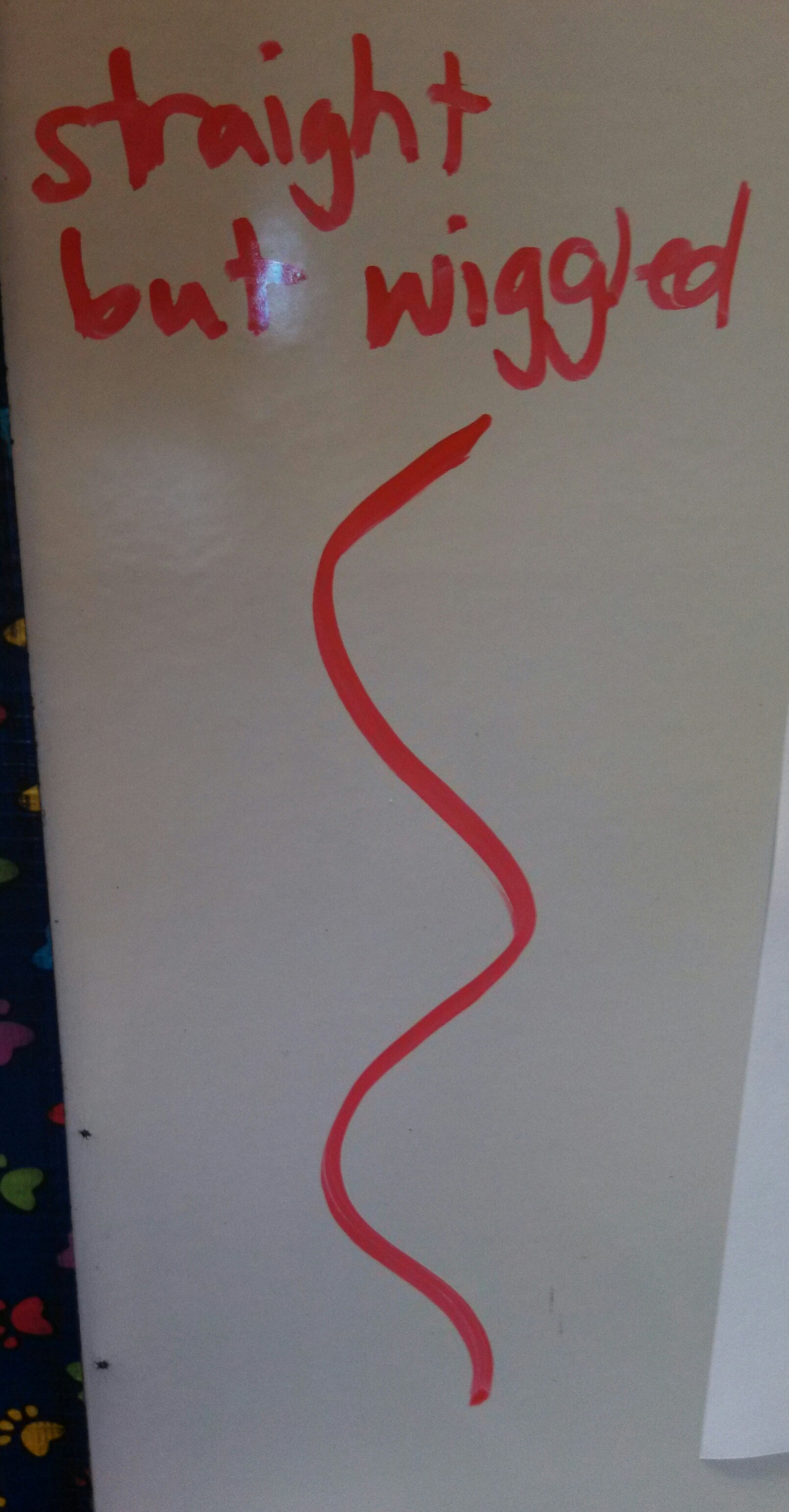

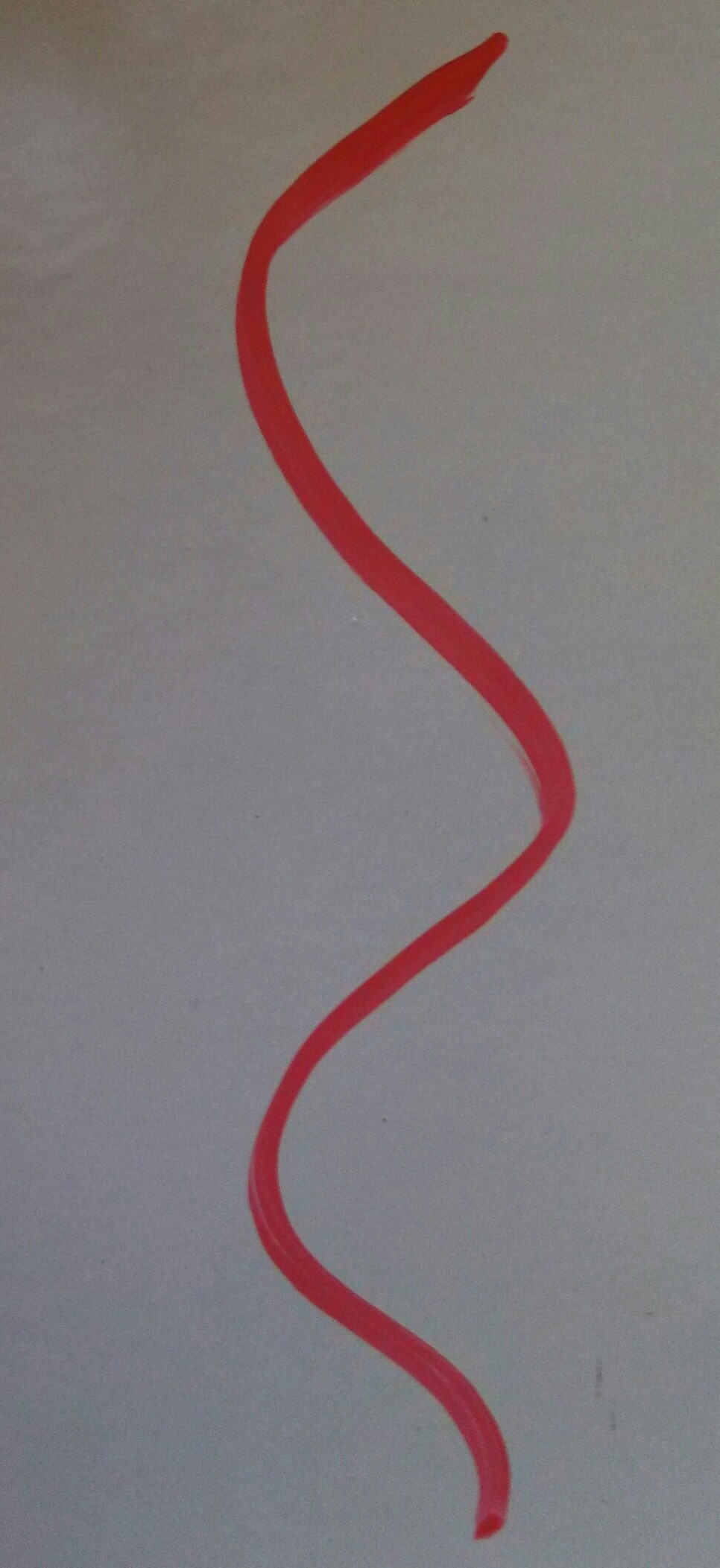

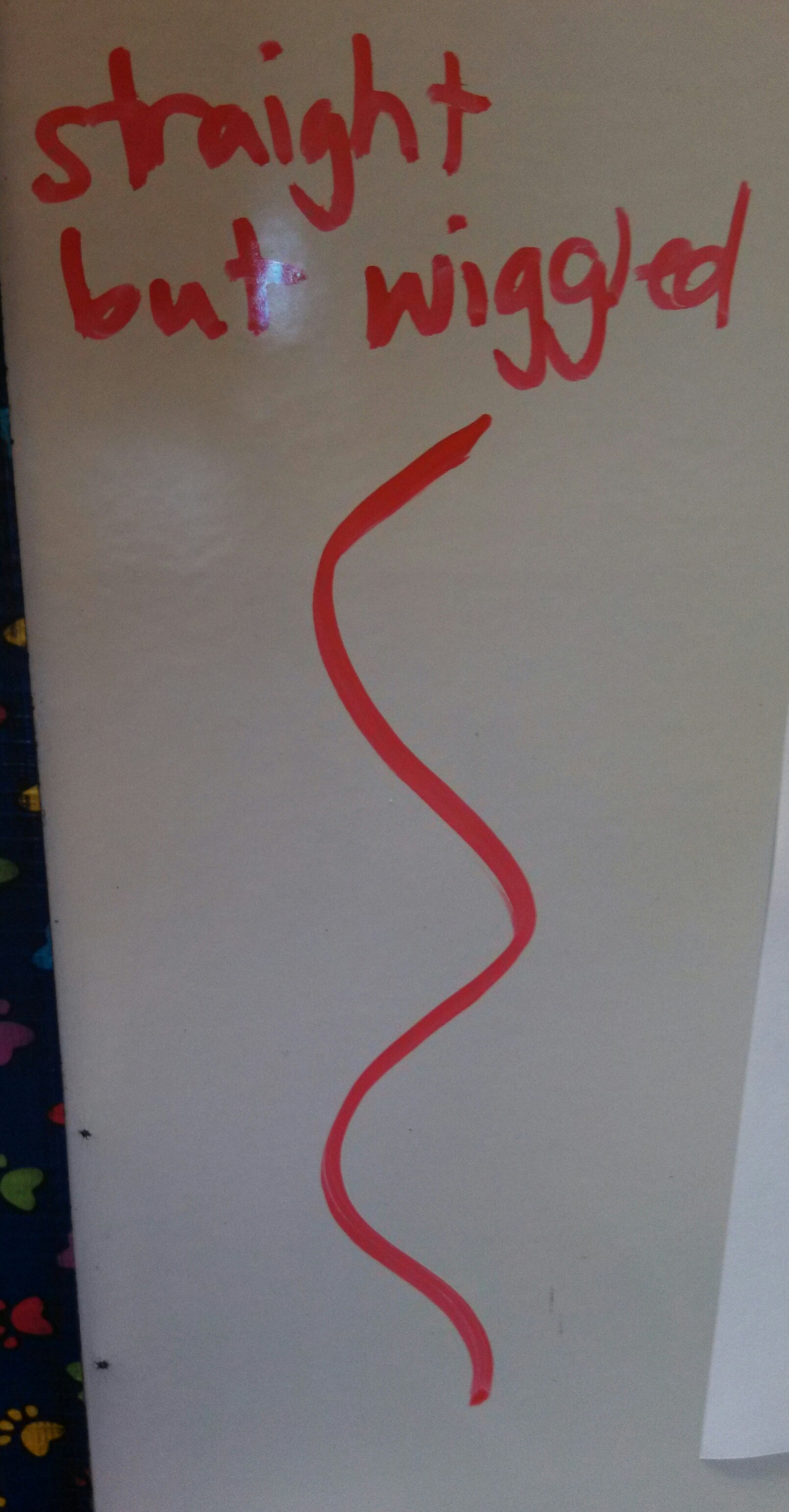

What about this one?

“That’s straight but wiggled.”

Oh man. How awesome is that?

The kids started arguing, in the best sense of the word.

Willy: “I don’t think that’s straight. Straight means it doesn’t have any wiggles or curves.”

Julie: “No, straight means it goes up and down. It doesn’t matter if it’s curved.”

Those were the clear terms of the debate. So now what do I do? I have Christopher on my shoulder still.

I have come to understand that talking about this difference is more important than defining it away.

I also have the knowledge that defining it away isn’t going to convince Abby or Julie or Mario. They might say “OK” to please the teacher, but I’m not going to change any minds that way.

At the same time, my mind is reeling, wondering how we use this word “straight” informally? Why have kids inferred that straight means up-and-down?

“Kids, line up in a straight line.”

“Sit up straight.”

“That picture is crooked. Can you straighten it?”

“Put the books on the shelf so they’re straight.”

In our everyday language, we sometimes do use “straight” to mean upright or vertical or aligned. I didn’t think of all these examples on the spot, but in the moment, I was confident I would think of them later. In the moment, I knew Abby had a good reason for her argument, based on her lived experience, even if I hadn’t figured it out yet. That faith in her sense-making matters a lot in this interaction. Her understanding of “straight” isn’t wrong; it’s incomplete. My job is to help her layer in nuance and context to her understanding of “straight,” so she knows what it means in an informal sense and what it means in geometry.

With the kids, I told them it might help us communicate if we added a few other words to the mix. I asked if they knew the words vertical or horizontal? They did, Abby included. They were able to correctly match the lines to the word.

Abby said, “I think there should be more words for lines.”

“Like what?”

“Like, vertiwiggle. That would be up-and-down and wiggled. And horizontawiggle for lying-down lines that are wiggly.”

This was the moment to stop pressing. That much I knew.

By coining these new words, Abby had let me know she was now thinking about two different attributes at the same time: the orientation and the wiggliness. I wasn’t about to resolve that complexity or define it away. I wanted her to think about it. I’ll check in with her next time and see what she thinks.

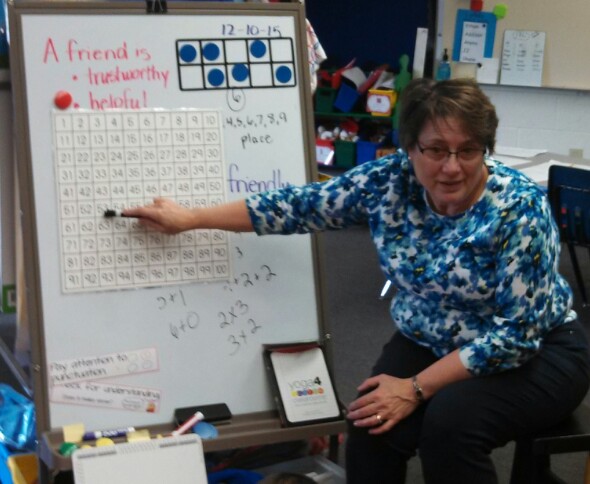

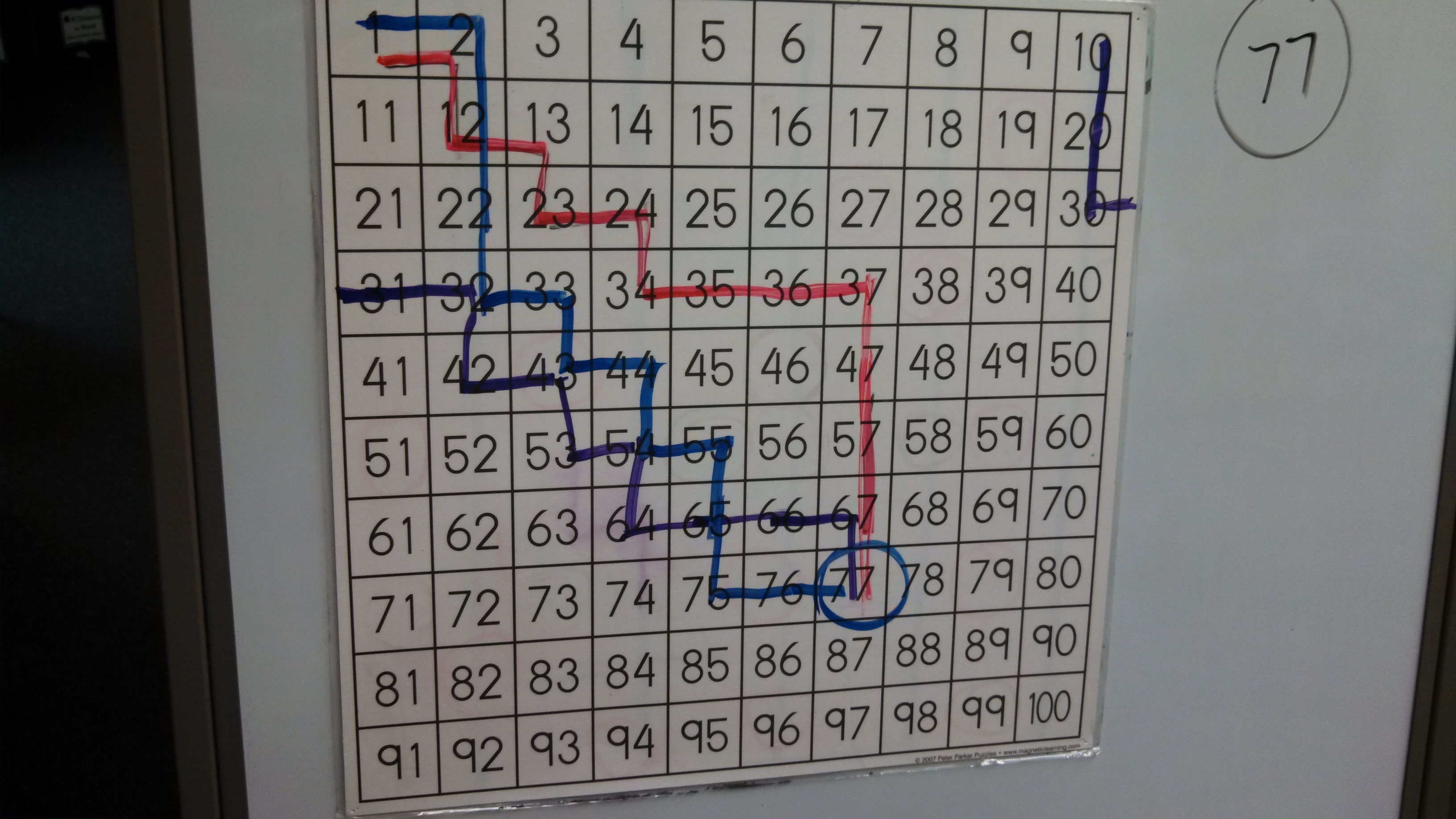

The classroom teacher said her mind was blown by this conversation. She had the whole class join us, and I erased the board. I used a straightedge and drew only the straight, vertical line. The whole class agreed it was straight.

I drew the straight, horizontal line, and asked if it was a straight line. All hands went up, even Abby’s. I looked at her and said, “Tell me what you’re thinking now.”

“I’m thinking that, even if it’s lying down, it’s still a straight line.”

Interesting.

I drew the diagonal line. Now about half the hands went up. I called on a student who said it wasn’t a straight line:

“Well, it’s almost a straight line, but it’s slanted.” Lots of nods at this.

Nate said, “I don’t think it matters if it’s slanted. Straight means it’s not curved. That line is straight.”

Emma said, “No, straight means it goes like this.” She gestured up and down.

There were lots of furrowed brows.

I drew the squiggly lines and asked who thought they were straight. A few hands went up. Abby raised her hand halfway, then put it down. She said, “I made up a new word for that kind of line. It’s vertiwiggly.”

The class laughed. I smiled and capped my marker. Time was up.

The teacher wants me to come back Monday and pick this up again. So, where should I go from here?

Whatever I do, I’m in no rush to define this loveliness away.