You can now take a look at what I’ve been up to since 2011.  The preview for

The preview for

Becoming the Math Teacher You Wish You’d Had: Ideas and Strategies from Vibrant Classrooms is live. You can flip through the whole book, if you like, before deciding whether it’s a good fit for you and your colleagues.

The book’s imminence has me feeling reflective. Couple that with the regularity with which I’m asked, “So what was it like, writing a book?” and you have the makings of a long, navel-gazey blogpost. Here we go, for those who are curious. Pour some tea.

[Disclaimers. I have two of them. One, from an author’s point of view, I’m only speaking to my experience. Two, I now have the good fortune to see this process unfold from the other side of the editor’s desk, as a Math and Science Editor for Stenhouse Publishers. You should know I work there.]

What do I have to say?

Five years ago, I ended up on the phone with my editor, Toby Gordon, kind of by accident. I was working for a university here in Portland, supervising and coaching student teachers at a wild range of schools. I loved that work, and had done it for quite some time in Boston, mostly with Boston University, and a bit with Tufts University and the Boston Teacher Residency. After we moved to Maine, I thought I’d continue that work while my kids were little, and then return to full-time teaching. Politics and state budgets kinda blew my plans, though. My department at the University of Southern Maine (USM) was hemorrhaging high quality faculty and not replacing them. Adjuncts were brought in to teach methods for $3000 a class, which is downright insulting. I loved my colleagues and my students, but the writing was on the wall, and I started looking around for new work.

I reached out to Toby at Stenhouse to see if I could work for her as an outside reader or freelance editor. Toby came highly recommended by, well, pretty much everyone and most especially my math hero, Elham Kazemi. We hit it off on the phone, and eventually she said, “Yeah, you could do those things, but what about you writing a book?”

I asked, “About what?”

She said, “Well, that’s up to you; it’s your book. What do you have to say?”

Inarguably the second-best question I’ve ever been asked. (“Will you marry me?” is tough to beat.)

She sent me off to brainstorm. I created lists of ideas and sent them to her. Toby told me which ones had legs. Some had been done before. Some wouldn’t sell. Some were unfocused. And one stood out. I just went and found my email to her, dated 11/29/11:

I was just looking at my shelf and my eyes fell on the first edition of Mosaic of Thought by Ellin Oliver Keene and Susan Zimmerman. That book was so path-breaking in that it taught teachers to view themselves as readers, first; to explore their own reading and think about what great readers do before delving into how we might start to teach children those same skills and strategies. I started wondering if anything like it had been attempted for math?….Has anyone tackled teachers’ affects about math in a cozy, curl up by the fire, more intimate and friendly way like Keene and Zimmerman did for teachers’ affects about reading? Attempted to help wary teachers embrace the discipline of mathematics as adults, not by telling them I’ll hand them a bunch of blackline masters so they don’t need to be scared (or think), but by guiding them on an internal journey about their own thinking and math?

It evolved, but that was the genesis, right there.

Toby sent me off to read. I think new authors often don’t know how important it is that they read. I had so much to read. Marilyn Burns’s book about math phobia, everything Deborah Schifter ever wrote, especially the pair of What’s Happening in Math Class? Reconstructing Professional Identities books, everything from Ball, Lampert, Fennema and Nelson, Hersh, Gresham, Beilock. Journal articles, books, blogs. I read.

And I started writing. Toby would check in on me periodically to make sure I wasn’t just reading; I was also writing. Four months later, in March of 2012, I submitted a proposal. I nervously waited, hoping they’d say yes!

They said…maybe.

It stung, but I received useful feedback from the editorial board and three outside readers. I saw what they were saying, for sure. I needed to work out the balance between practicality and big ideas. I needed to figure out exactly who my reader was. I needed to be more positive, and not spend so much time stating the current problem. They asked for an additional chapter from classrooms, based on fieldwork I hadn’t done yet. In fact, I wasn’t really sure what my chapters were yet. I knew my Table of Contents would grow out of my work in classrooms and my research, and I had a tough time trying to nail it down before doing that work. I started to sweat committing to anything before I’d done the research, research I had to do with an open mind.

In other words, I was afraid I was losing the book for the sake of the proposal.

So I did something kind of ballsy. I told Toby I was going to pretend they’d said yes. I was going to stop saying, “If I write this book” and start saying, “I’m writing this book.” I’d begin fieldwork and mucking around and gathering information and literature reviews. When I’d done more of that thinking and legwork, I’d know where I was headed, and I’d be ready to resubmit a proposal with a full chapter.

She was tickled. And supportive, as always.

Your shift in thinking makes absolute sense to me. Rejigging the proposal and chapter now is like putting the horse before the cart. You’ve done a lot of thinking and reading about this project, but clearly there’s a lot more to come—plus you want to start tracking down and working w/ teachers. So, I’m all for it! I have no doubt this shift will serve you—and the book—well. Everyone has different ways of going after a book. You’re well acquainted w/ your non-linear approach—so just trust it and see where you land. I’m here whenever you need me.

The research

This is where my project looks radically different from most projects. Most of the time, people already have some idea what they’re going to say. Most of the time, their books grow out of the work they are already doing.

Not me. I didn’t have answers at that point, just questions. My main ones:

- What’s essential to the discipline of mathematics? What ways of knowing, coming to know, changing our minds, thinking, agreeing, and disagreeing are unique to mathematics?

- What would it take to make math class more like mathematics?

- How can we close the gap between math class and mathematics when teachers have never really experienced mathematics as it’s actually practiced?

- How can we improve the system when we’re the products of the system? What supports do teachers need? What could I offer teachers that would be useful?

- In The Process of Education, Jerome Bruner said, “We begin with the hypothesis that any subject can be taught effectively in some intellectually honest form to any child at any stage of development” (1960). This statement has been a core belief throughout my career in education, and I treasure my copy of that little red book. But what does “intellectually honest” math look like to students at different stages of development? And how do we facilitate that? (Curious? Ball dug into this question a bit in her With an Eye on the Mathematical Horizon article.)

- What’s replicable? When I find teachers who are teaching math class so students are doing the real work of mathematics, will I be able to help other teachers learn from them? How?

I read a ton. I also hit the road in the fall of 2012, working around my teacher ed schedule at USM. I started visiting classrooms, asking for recommendations of great math teachers in a variety of settings. I started with 40 names, and observed and interviewed them all. I saw a lot of very skilled teachers, but I quickly came to realize that what I meant by the phrase “great math teacher” wasn’t what other people meant by “great math teacher.” For me, that phrase wasn’t code for good management. Or high test scores. Or clear explanations. Or “fun” activities.

I meant something bigger. Different. Something about how the kids were interacting with the mathematics, and each other, and the teacher. Something about the combination of joy and intensity, curiosity and passion, safe exploration and high standards. Something about the transparency of the raw thinking, and the way math felt empowering. Something about who owned the thinking, who owned the truth, who owned the authority to decide if an argument was convincing.

I first found what I was looking for in Heidi Fessenden‘s 2nd grade classroom in the Mattapan/Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, MA, and in Shawn Towle‘s 8th grade classroom in Falmouth, ME. I couldn’t get enough of these two. They teach in totally different grades, different settings, different student populations, with different curricula. They’d never met or taken a course together and have taught for different lengths of time; yet, somehow, when Shawn opened his mouth, he said just what I’d heard Heidi say. When Heidi looked at a piece of student work, I saw the same wheels turning I’d seen in Shawn. When a student made a mistake with lots of potential to dig down into understanding, the same delight came into their eyes. I started spending as much time as I could with them.

It was through months of conversations, observations, and interviews with Heidi, Shawn, and their students that I started to figure out what my book really was about. I grounded my ideas in classroom realities and started identifying these teachers’ most practical, replicable, effective techniques. I started seeing what “intellectually honest” mathematics teaching and learning looked like in different content areas, with different aged students. Mostly, I started putting to words what made me so darn happy in their classrooms.

Around that time, I broke my ass. I’m not kidding. I was walking our two big dogs on an icy morning and they pulled at the wrong moment and I looked very much like Charlie Brown when Lucy snatches the football. I fractured my tailbone and had to call off my observations for a bit because I couldn’t sit in the car or on the train.

That was early December, 2012, and I was suddenly stuck at home with my laptop. I let Toby know I was starting a new proposal. I’d learned so much since the last one. This time it flowed. This time I knew where I was headed. By February, I had a chapter and revised proposal ready to go. I submitted, and this time the editorial board and reviewers were unanimous in accepting it. I was under contract to write a book in March of 2013.

In the meantime, I’d kept researching, reading, and looking for other teachers. That’s how I found Jennifer Clerkin Muhammad that May. She taught fourth grade in a two-way bilingual school in the South End of Boston, and she rocked my world. The level of discourse in Jen’s room was astounding. My regular trips to Boston to visit Heidi now became trips to visit Heidi and Jen. Jen taught in the morning; Heidi in the afternoon. Their schools were across town from each other, but it was doable. I’d take the 5AM train out of Portland, visit both teachers, crash with my friends Shoma and Josh, visit both schools again the next day, and catch the nighttime train back to Portland. I loved those trips so much. Riding back on Amtrak, I’d have dialogue and images and questions and student work whirring in my head and on my computer. I’d play back the video for a bit, and then stare out the window at New England going by, and think. What, exactly, were the instructional decisions the teachers made and techniques the teachers used to engender such amazing mathematical communities?

I still felt like I needed a small-town setting, because so many of my examples were urban and suburban. I kept looking, and that’s how I found Debbie Nichols, in rural NH, in August of 2013. From my first day in Debbie’s room, I knew I’d found a home. I started spending every Tuesday with Deb and her young students, and I learned something every time I visited. Still do.

Heidi, Shawn, Jen, and Deb are the four anchors of the book. They were the teachers who helped me figure out the core of what I was trying to say. I also visited dozens of additional teachers who were fantastic and added new voices and stories and teaching challenges and opportunities. You’ll meet lots of them in the book as well.

Writing

This header is a little misleading. I didn’t do all the research and then do all the writing. Both were happening all the time. But I did frontload the research and then really dig down into the writing.

I loved writing this book. I mean, I loved it. It was my trusted companion for years. I thought about sections in the shower, chapters when I was falling asleep at night, a better way to close that story while walking the dogs. With every revision, I got clearer about what I was saying, about what mattered. It was hard. It was a worthy problem, though, and I enjoyed the challenge. Some days I struggled all day and still barely filled my one-inch picture frame. Other days, I found some kind of flow, and I could hardly sleep because I was reworking and moving and dreaming about passages.

Throughout, I counted on Toby. I sent her chapters and bits of things as they were ready, when I needed feedback. She’d tell me what she loved, and I tried to do more of that. She’d tell me when I was dropping in too much research, and I’d cut. Some. Ha! She’d tell me if she got bogged down in the details or if something didn’t make sense, and I’d clean it up and prune it back. Throughout, it was clear it was my book, and I could take or leave her suggestions. I took most of them. Sometimes I argued back, and she would come around to seeing why I felt I had to do something a certain way. Sometimes, months later, I’d realize she’d been right all along and change it. She never gloated about those moments, which was gracious.

Something I’ve learned since becoming an editor: there’s a duality at the core of our work. We take tremendous pride in the books we publish, but we’re egoless during their publication. It’s our job to make the authors look as good as possible, to help them say just exactly what they want to say in the best way possible, to usher their books out into the world as effectively as possible. But we erase our fingerprints from that work. The author is the one who shines; the editor works behind the scenes. The book is the author’s baby. The editor is the midwife. Both roles are immensely satisfying.

I took a master class in editing by being edited by Toby. I apprenticed with the best.

We emailed, we texted, we talked on the phone, and we met for lunch sometimes (because we live in the same place, lucky me!) to discuss my progress over fish sandwiches. I always walked away clearer on what I needed to do, or at least what the terms of the struggle were. Often I’d be halfway through an email to her and I’d realize the solution to the problem I’d been describing.

I like feedback a whole lot, so I also sent chunks of the manuscript out to other people. I sent every chapter to all the teachers named therein, and I wouldn’t go forward without their approval. I also sent chapters to experts on specific sub-topics. Reuben Hersh read my work on intuition. Danny Bernard Martin read a section on equity. Virginia Bastable helped me with representation-based proofs. In each of these cases and many more, people were generous with their time, expertise, and insight, and I am indescribably grateful.

I was interrupted during the writing of the book. Cancer is rude that way. I thought I’d be able to write during my mom’s treatment and mine, but I wasn’t. I made it through that year watching back episodes of Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, walking the dogs in the woods, staring out the window, and reading The Princess Bride on a loop. You do what you gotta do. Toby told me to write if it helped me cope, and not to write if it didn’t. I couldn’t. All I could manage to write during that time were tweets. Thank god for twitter, and my friends there.

When I was able to come back around to the book, I fell in love with the process of writing something long all over again. I love building a larger argument, thinking about how to guide the reader through it, crafting a larger story. I wrote the last word on the last page in December of 2015. I celebrated for an evening, and then I turned back to the first word on the first page and started revising the next morning.

Revision

Again with the misleading header. I’d revised all the way through. Every time I worked on a chapter, I’d start at the beginning and work my way toward where I’d left off. Some days, I never got past the first page. Revision-during-writing is essential.

But once the whole thing was drafted, I got to focus exclusively on revision, and that was extremely satisfying. Time had made it much easier to cut unnecessary words, quotes, and examples. Writers say “Murder your darlings” for good reason. Some of my darlings had become less dear over time, and knocking them off was much easier after a bit of distance.

I’d also discovered I’d gotten better at writing the book as the book went on, so I went back and revised the early chapters to match the later ones. Interestingly, this often meant writing with more confidence than I had at first. First-time authors are often uncomfortable saying, flat-out, what they think. That got a lot easier for me with practice.

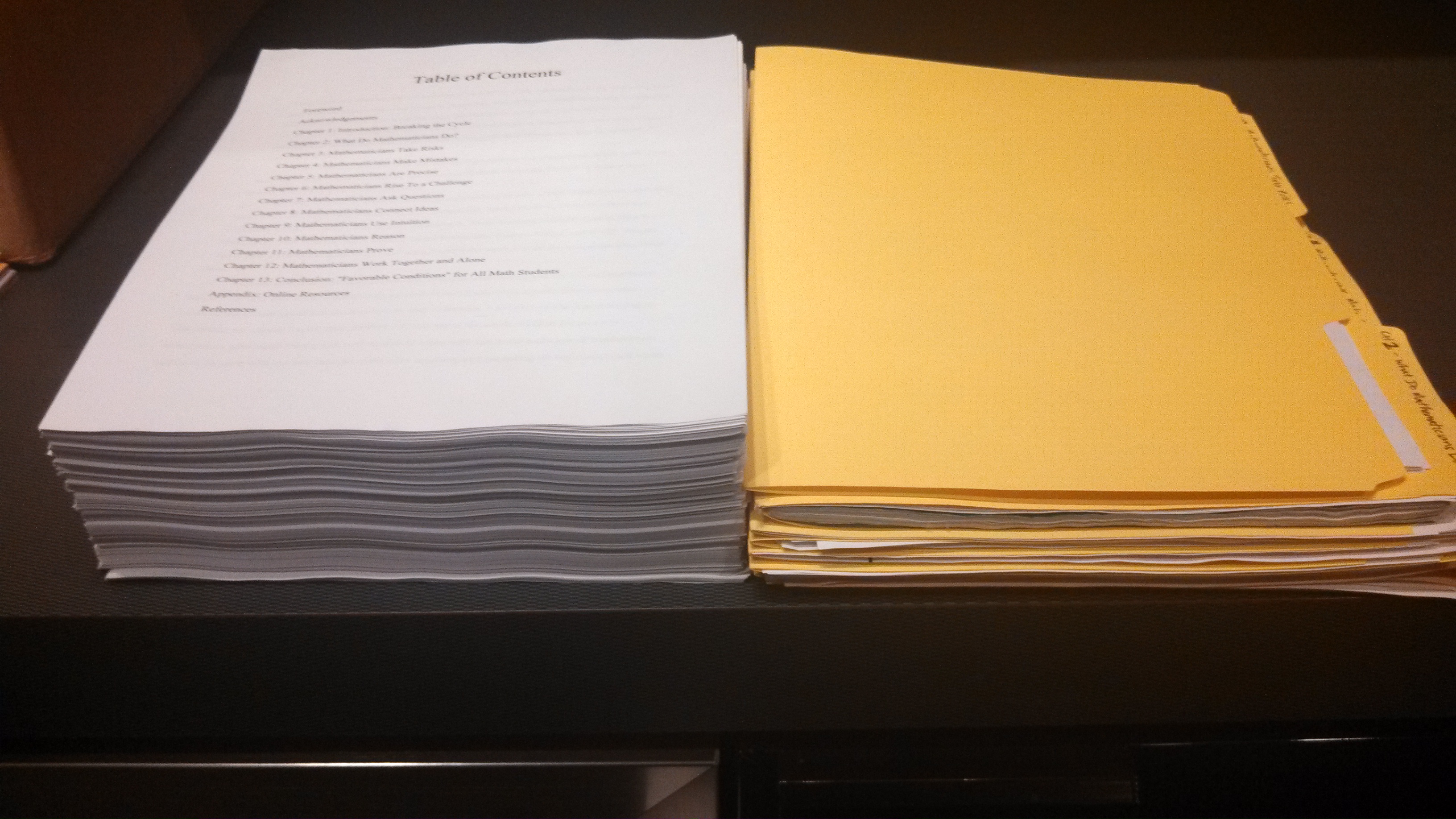

A big part of revision was working on the artwork. Throughout the writing of the book, I’d collected all the high-resolution photographs and original student work I thought I might use, along with permission slips from parents. I accumulated a giant box, and then slo wly trimmed them down to the most essential figures. No fluff! At the end, it was time to number those figures, insert design notes in the manuscript to show where they should go, build the art chart for the production team, make sure all my permissions were in order, put sticky notes on student work saying when names needed to be removed or ancillary problems needed to be cropped out, and so on. I made an efile and file (the yellow folders in that picture) for each chapter, and organized all the figures carefully.

wly trimmed them down to the most essential figures. No fluff! At the end, it was time to number those figures, insert design notes in the manuscript to show where they should go, build the art chart for the production team, make sure all my permissions were in order, put sticky notes on student work saying when names needed to be removed or ancillary problems needed to be cropped out, and so on. I made an efile and file (the yellow folders in that picture) for each chapter, and organized all the figures carefully.

Getting Ready for Turnover–The Team Grows

When everything was as done as I could get it, I handed the whole pile and files to Toby. She started back at the beginning and read the entire manuscript again. When a change was needed or something could be cut, she flagged it. When she was ready, we met again and went through, sticky note by sticky note, making decisions together. We pulled some figures, which meant renumbering again. Most of the changes were quite manageable, though.

Once I cleaned up the files, the manuscript was ready to be turned over to the production department. Turnover is a slightly misleading term, because the editorial work is not over. Toby stays with the project from that first nervous phone call until well after the book is out in the world. But at turnover, the team of people working on this project grew from the two of us to a whole group of people. Just the briefest of descriptions:

- Production Editor Louisa Irele carefully worked through every figure and picture, scanning original work, correcting my errors, and checking permissions. She went through the text files and put them in mansucript form.

- Editorial Production Manager Chris Downey is responsible for everything that happens with the text from turnover to publication. She handles the words. She is incredibly kind, professional, and knowledgeable–I swear, the complete Chicago Manual of Style resides in her head somewhere. She has enviable attention to detail. The designer of my book told me he can pick out Chris’s manuscripts from the ones he receives from other publishers. The quality of her editing is remarkable. Chris guides each manuscript through copy editing, typesetting, multiple rounds of proofreading, and indexing with care.

- Obviously, that means we have professional copy editors, typesetters, proofreaders, and indexers on this team as well. I am so grateful for everyone’s eagle eyes! When I got nervous about mistakes, Chris reassured me. “Don’t worry. We have six pairs of eyes looking at these proofs right now.” It helped.

- Jay Kilburn is the Senior Production Manager, and he handles the design of the books. We never use templates at Stenhouse; rather, each book is individually designed. Jay is so gifted at pairing authors with the right designer. Take a look at Which One Doesn’t Belong? It’s so Christopher. And my book is so me. It’s amazing! Jay works with the designer on the overall feel of the book. They decide on the trim size, the covers, the fonts, the headers, all the design elements in the interiors (boxes, sidebars, pullquotes, tables, chapter openers, running heads, dialogue, etc.). Jay also manages the actual production of the books at printers, binderies, and warehouses. He has this huge realm of knowledge about glues and sigs and press runs and where the readers’ eyes need places to rest and widows and orphans and kerning and spot varnish. (Look at the covers of Which One Doesn’t Belong?. See how the shapes have a bit of shine that makes them pop? That’s spot varnish.) I’ve been at Stenhouse just about a year, and I’m at a place where I can begin to grasp the deep knowledge of bookmaking that Jay has, or at least get most of the vocabulary.

- Lucian Burg designed my book. He also happens to be a lovely person and one of my neighbors! We hire local whenever possible, and Lucian is really local. A few weeks ago, the girls and I stopped by his studio to drop off page proofs. Lucian told me, “I’m proud of your work and I’m proud of my work,” which made my day. He loves converting these ugly word processing files into a beautiful, visual, satisfying experience for the reader. His studio might be the prettiest workspace I’ve ever seen, largely because its filled with the beautiful books and covers he’s designed. Throughout this project, he understood the feel and vision I was after, and I couldn’t be happier with what he did. It’s a perfect marriage of content and design, which is the whole goal.

So, at the turnover meeting, the editor helps the production team get a feel for the book and its style, as well as any particular themes or ideas that might translate visually. Production then gets to work.

People kept thinking I was done at this stage. Nope. The manuscript came back to me two more times: once after copy editing and once after proofreading. Jay also sent initial design files to see if I liked the way the designer was approaching the book. Did I like the way he handled the different elements of the text, like dialogue, block quotes, captions, etc.? You bet.

While I missed writing the book, I mostly loved this phase. What had been my project was now our project. Every person was adding his or her expertise and knowledge and skill to this effort, and together they took my pile of files and folders and documents and turned it into a book. I am in awe of my production colleagues and the work they do.

Getting Ready for Publication–The Team Grows Again

As publication appears on the horizon, the marketing, sales, operations, and customer service departments get involved with the book. Without giving away any trade secrets, I’ll say the marketing team puts together a specific plan for this book, based on its strengths, the author’s desires, and their robust knowledge of the market. They get the catalog ready, the product page launched, and the advertising lined up. The sales team starts educating our regional representatives about this book so they can begin talking it up in schools. The operations team works with Jay to make sure the book moves from the bindery to the warehouse on time and properly packaged, so it’s ready to ship out on day one. Customer service, sales, and operations together work with readers, teachers, school districts, booksellers, and international distributors. From preorders to purchase orders, they are experts in the business of publishing, and they are the ones who get books into your hands.

Out It Goes, Into the World

The team is about to get a lot bigger, and change again. We’re about to add readers.

This is the mind-blowing part. Toby has always told me that books take on lives of their own once they’re published. You plan and you try and you hope and then you send it out there and see what happens.

I had the best time writing this book. Selfishly, it was worth every minute. But I didn’t just write it for me. I wrote it for you. I expect some of you will like it, some will not, some will agree, some will disagree, some will be put off by the length, and some will want more. All good. What I hope above all else, though, is that it will make you think. Hard. It’s jam-packed with ideas, and I hope you’ll find yourself reflecting on them as you take a shower or chop tomatoes into your salad. Whatever you decide about the arguments I make, I hope this book helps you teach with intentionality and joy.

I have one last bit of work to do before it sets sail. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be adding some dedicated spaces here and on social media about the book. Here, there will be a site for each chapter, along with a robust study guide, supplemental resources, calls to action, and all that good stuff. I haven’t worked out the tech yet (#growthmindset), but I will be building forums for discussion throughout those sites. I’m most eager for those forums, because I’m jazzed to hear your reactions. I wrote this book to move the conversation forward, not have the final word. I can only get wiser if you educate me.

I must really want that dialogue, because I’m even willing to establish a book study page on facebook. Oh my.

So once I get the spaces built, please stop by and tell me what you’re thinking about in response to the book. What new questions are you asking? What are you trying in your teaching? What did I get wrong? What should I be thinking about next?