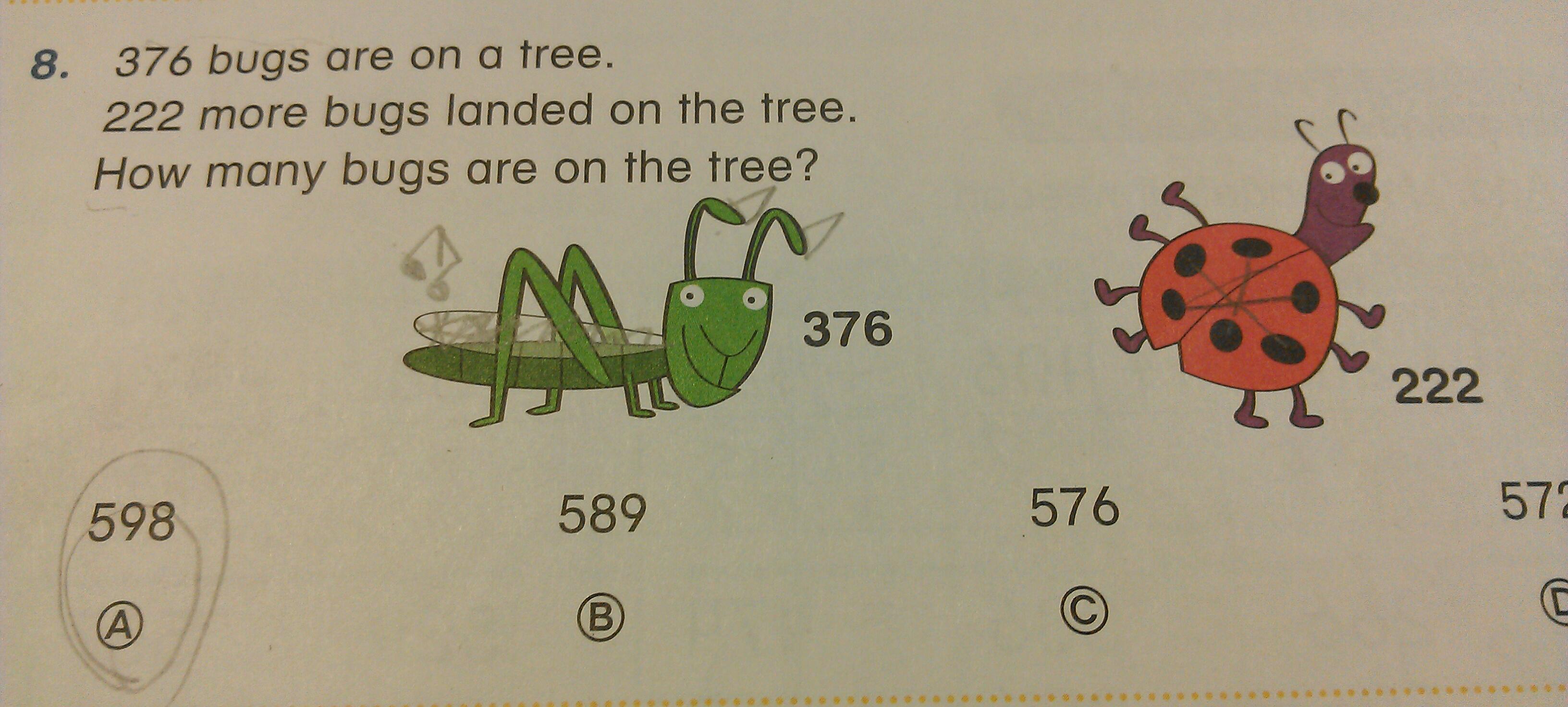

Maya (7) brought home a folder full of completed math worksheets yesterday, which put me in a funk. First, there was the bugs problem.

I couldn’t decide which part of this problem bothered me most. Was it the ridiculous premise? I mean, come on. Was it that the problem was, yet again, a multiple-choice question? Was it the stubborn insistence on drawing bugs with the wrong number of legs? Was it that students have no room to work, but the publisher took plenty of room for cutesie drawings? Harumph.

I couldn’t decide which part of this problem bothered me most. Was it the ridiculous premise? I mean, come on. Was it that the problem was, yet again, a multiple-choice question? Was it the stubborn insistence on drawing bugs with the wrong number of legs? Was it that students have no room to work, but the publisher took plenty of room for cutesie drawings? Harumph.

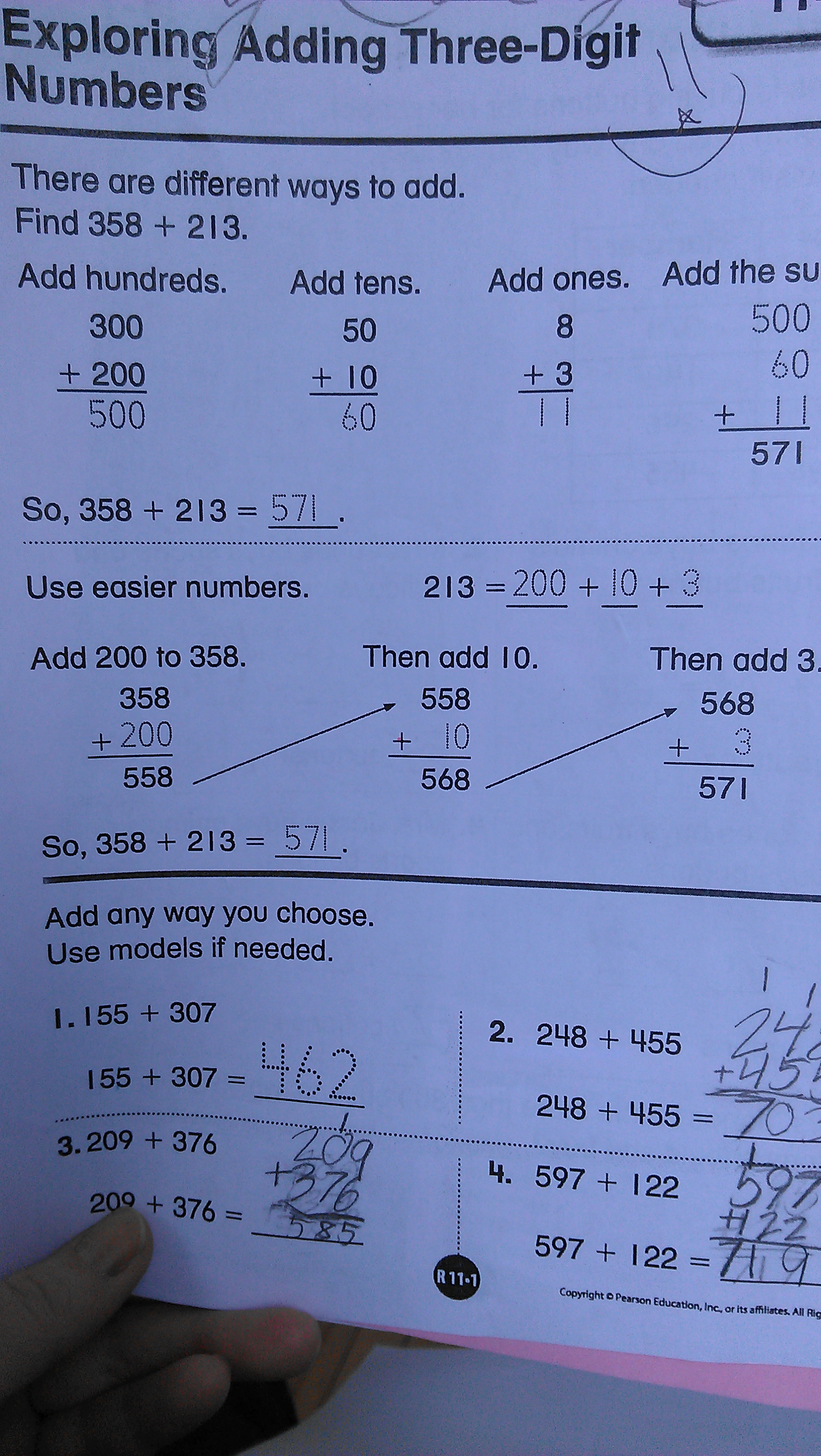

As awful as the bugs problem was, the page that really upset me was this one:

- The strategies are named wrong, and made to look more complicated than they are.

- There are better and other ways to solve this problem.

- Students are left with 2″ to do math on this entire page, which is barely enough room to do the standard algorithm. There’s no chance they’ll try out one of the other strategies with no space to work.

- Once again, we’re turning useful, general computation strategies into prescriptive algorithms. Breaking the numbers up by place value and adding the partial sums becomes: Step 1) Add hundreds…

I’m not the first math teacher to notice that prescriptive worksheets are a problem. Kamii, the CGI group, and others have all written about it. Yesterday, though, I was upset as a parent because Maya has stellar, flexible mental math skills, and her instinct to think is being undermined by this curriculum. I asked her why she’d opted for the standard algorithm on all the problems, and she said, “Those other strategies are too confusing.” I covered up her solution to 597 + 122 and asked her to solve it mentally.

“Well, I’d give 3 to the 597 to make it 600. Then 600 + 122 is 722. I’d take the 3 back, so it’s 719.”

I did the same thing for 209 + 376:

“200 + 300 is 500. 500 + 70 is 570. 9 + 6 is 15. 570 + 15 is 585.”

I pointed to the top of the page and said, “You just used this strategy. You broke the numbers up into place value parts, and then added each part together, starting with the biggest part.”

Her jaw dropped.

And my mind clicked. She has made NO connection between the mental math strategies she uses with fluency and all this junk on the worksheets. The reason? She’s never been given the chance to record her own thinking at school.

I think I’ve decided what one of my bigger problems with this curriculum is: they never use blank paper. They never write 209 + 376 at the top of a big piece of paper and let kids have at it. The kids never get a chance to wrestle with keeping track of their thinking or figure out organizational strategies. All math problems are either on worksheets or educational technology. The kids just don’t write enough.

So now I know what to do with Maya at home. We’re going to spend some time with blank paper, where she has to work out how to write down what she does in her head. She needs to make mistakes, lose track, not be able to follow her own thinking, and then ultimately figure out ways that make sense. She needs to be able to write down her thinking so that she and her mathematical community can follow it. I’m on it.

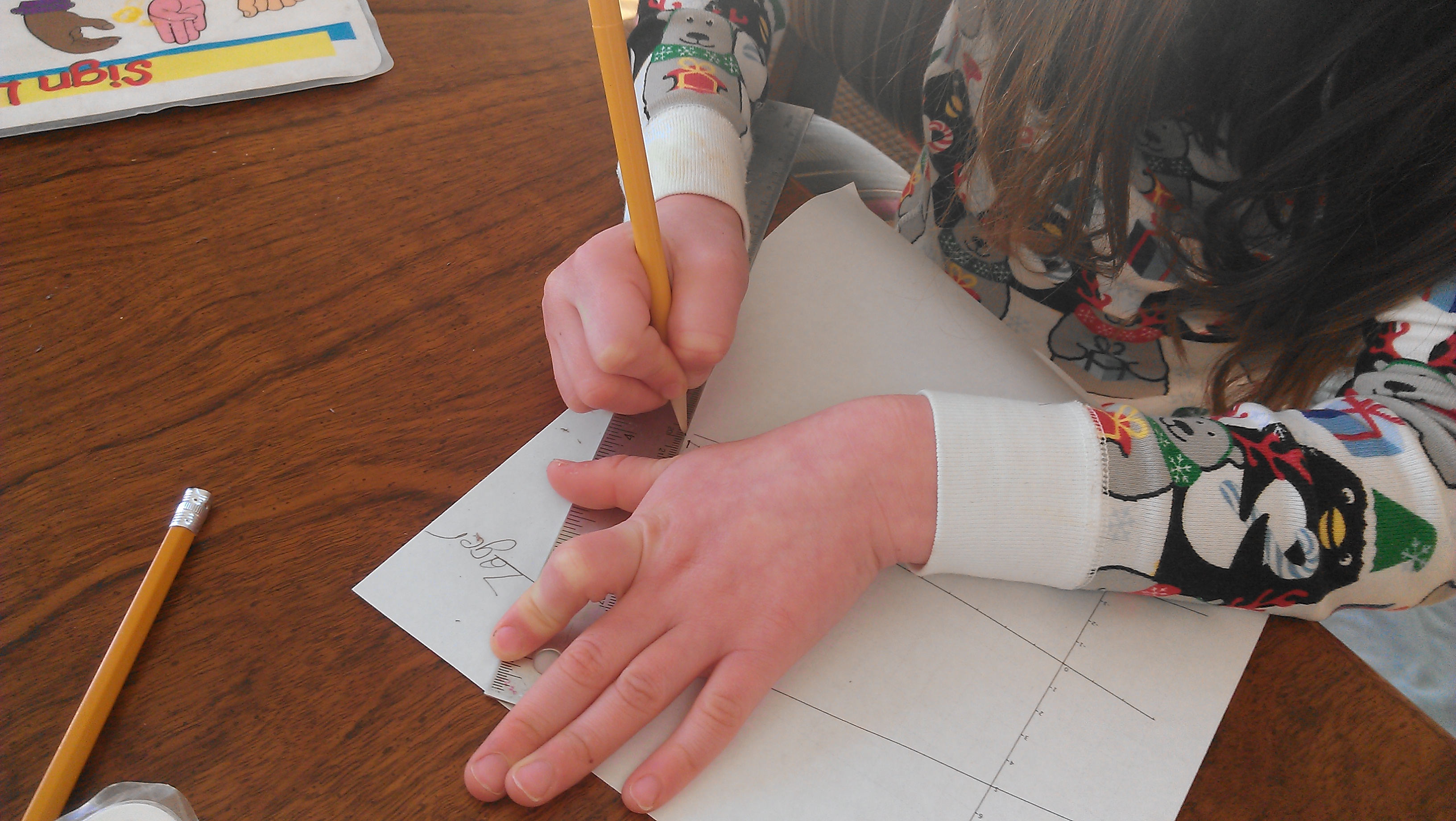

Two hours later, after dinner, Daphne (5) got us started. Our dining room chairs have decorative nailheads, and the kids are forever running their fingers over them and counting them. Daphne said, “Someday, I’m going to get out a math journal and count all these nailheads and write it down so I know how many there are.” Before I knew it, she was off! Someday turned out to be right then. Both kids got in the game.

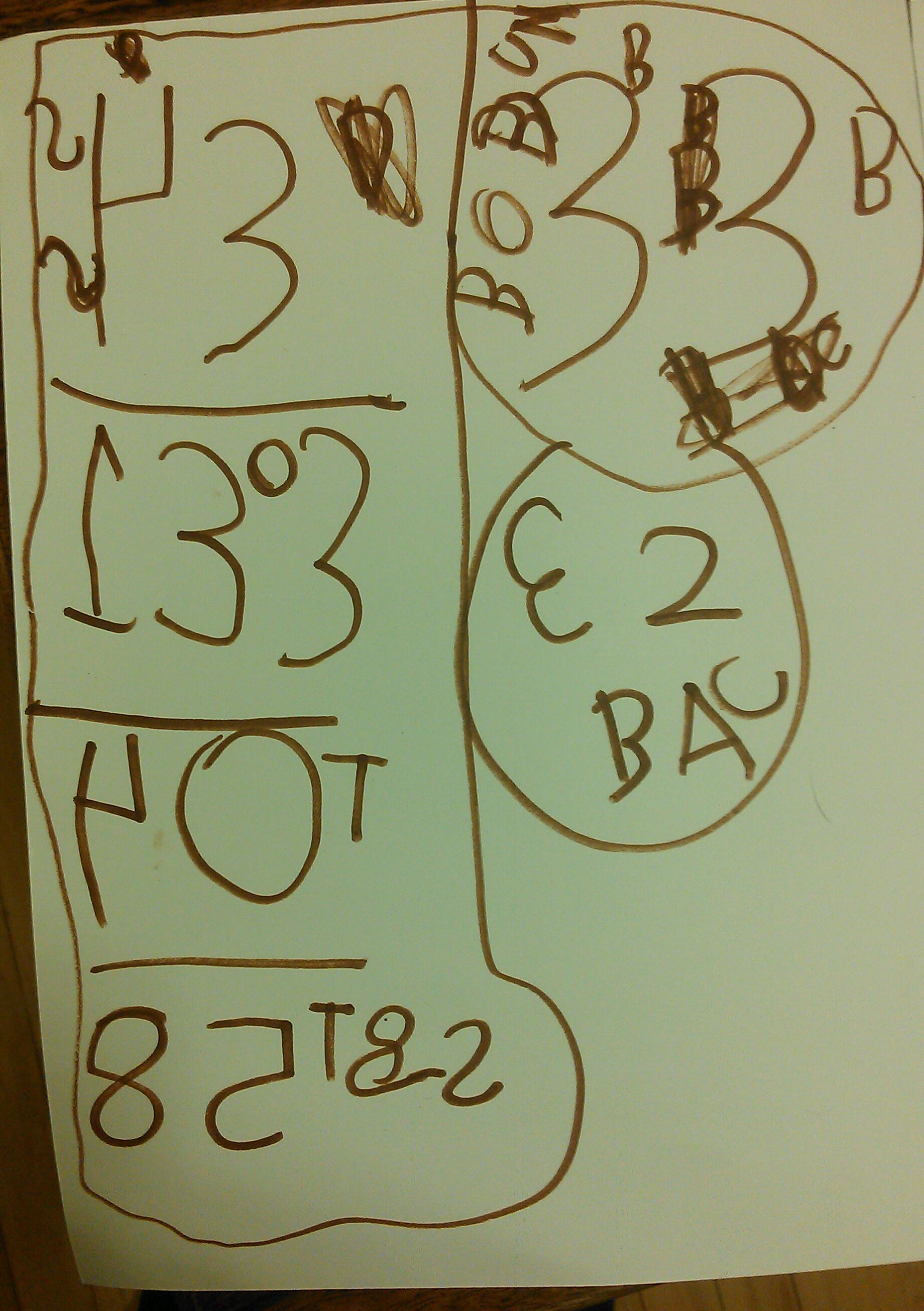

Daphne was incredibly excited to count AND write down her results. Check them out:

If you want to understand her notation, take a peek at the short videos:

If you want to understand her notation, take a peek at the short videos:

The power of blank paper, baby.

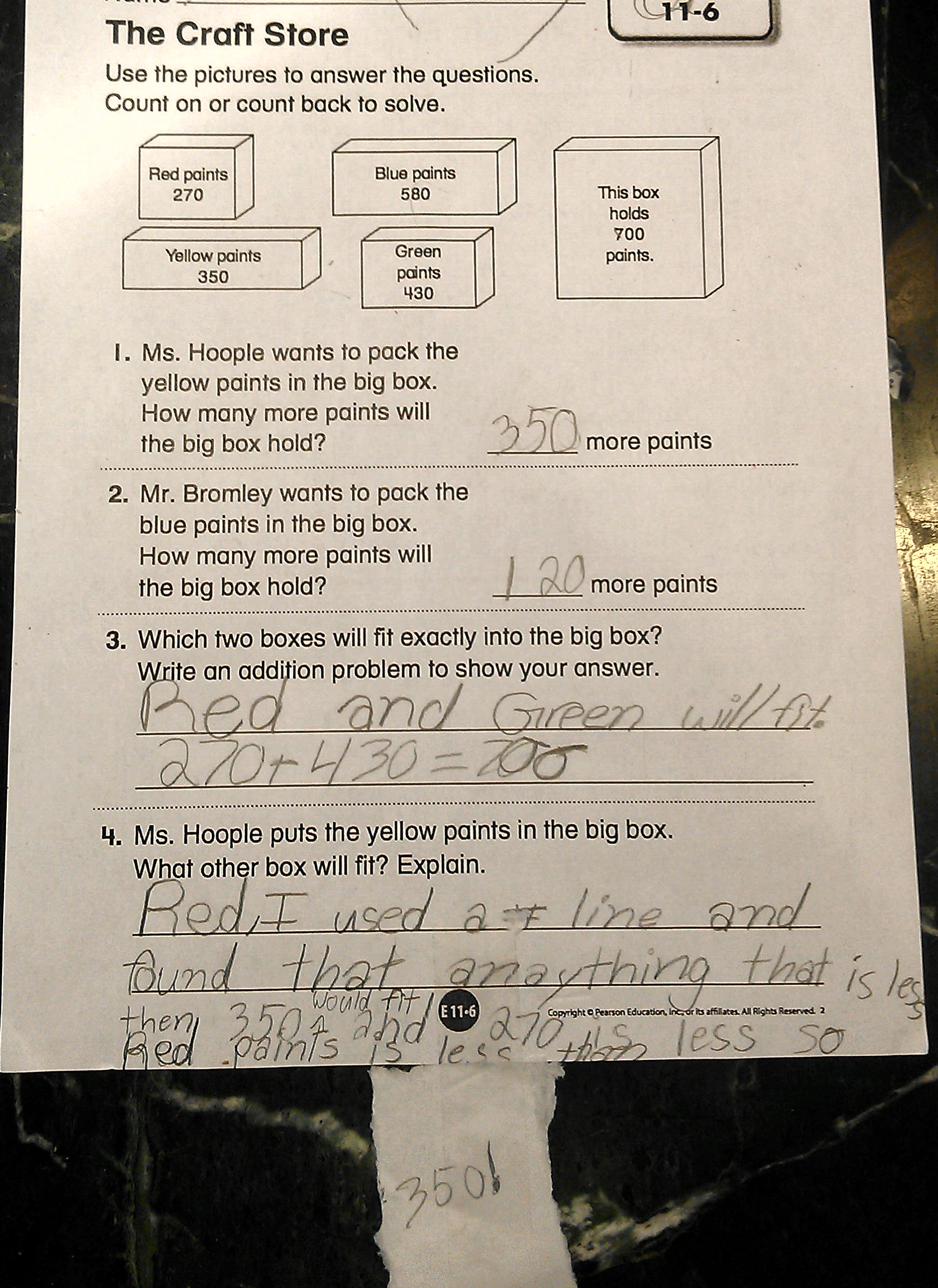

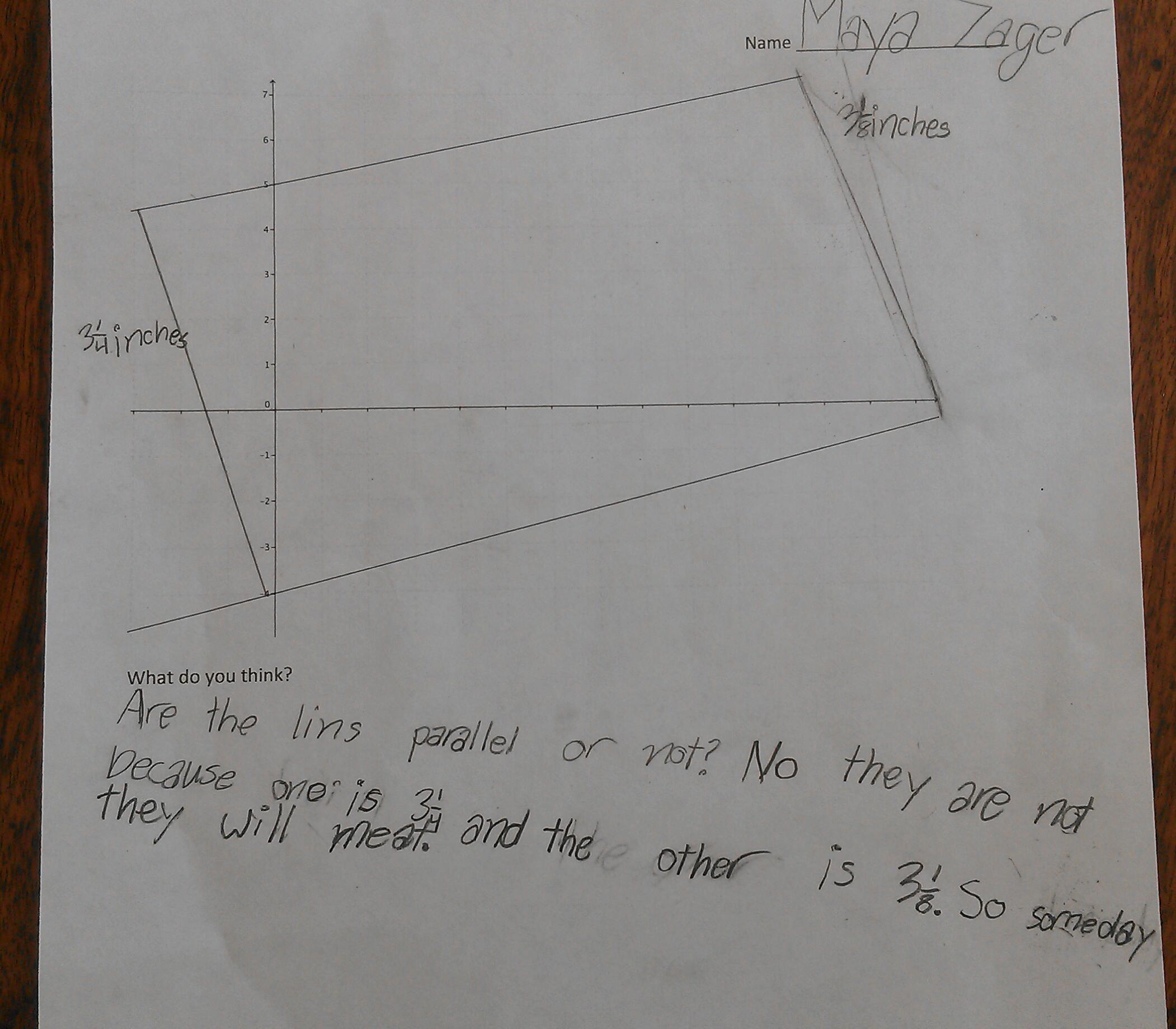

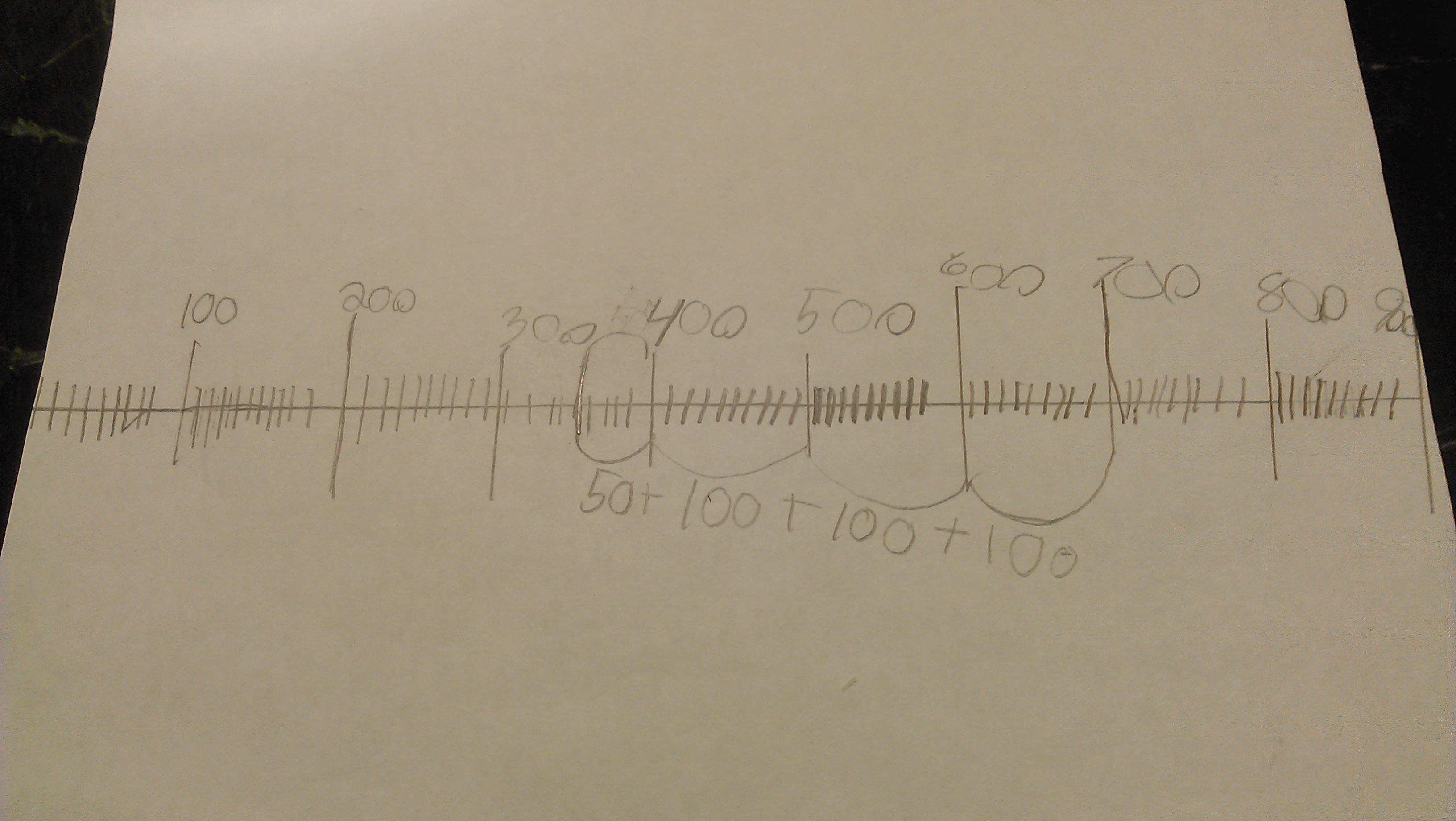

Perhaps inspired by all of this discussion and my venting, Maya asked if she could get a piece of blank paper when she did her homework, which is truly a counter-cultural act with this curriculum. “Of course!” I nearly sang.

She created this number line and used it to solve the final problem.

When I asked her about it, I pointed out that she didn’t just answer the question by saying, “The red one.” She wrote about the problem more generally: “I used a number line and found that anything less than 350 would fit and 270 is less so red paint is less than 350!”

When I asked her about it, I pointed out that she didn’t just answer the question by saying, “The red one.” She wrote about the problem more generally: “I used a number line and found that anything less than 350 would fit and 270 is less so red paint is less than 350!”

She said, “Well, when I wrote it myself I thought about it more.”

Precisely my point.